CL&A-Cincinnati, Lawrenceburg & Aurora

Electric Street Railroad

Anderson Ferry - Aurora, IN, branch to Harrison

1900-1930

Standard Gauge

Constructed by the Cincinnati Lawrenceburg

& Aurora Electric Street Railroad, 1900

Reorganized as the Cincinnati

Lawrenceburg & Aurora Electric Railway Company, 1928

Purchased by Cincinnati Street Railway, service

cut back to Fernbank, line from Anderson Ferry to Fernbank

converted to broad gauge, 1930

Streetcar service suspended, 1941

This interurban was a standard-gauge line along the

Ohio River from Anderson's Ferry, at the west end of Cincinnati,

to Aurora, Indiana (25 miles), with a branch from Valley

Junction to Harrison, Ohio (8 miles). It was completed in 1900.

Plans for extension west to Rising Sun, Madison, and Louisville

were never implemented. In 1913 flood damage forced the road

into receivership, from which it did not emerge for 15 years,

one of the longest receivership periods in the industry's

history. The line is principally noteworthy for its pioneer

purchase of lightweight, one-man equipment in 1918. The company

was severely handicapped by its remote terminal, but like the

rest of Cincinnati's standard-gauge interurbans, it never

achieved entry into the center of the city. After reorganizing

as the Cincinnati Lawrenceburg and Aurora Electric Railway

Company in 1928, the line survived for only two years, and was

abandoned in 1930 after a year of operating losses. Six miles

from Anderson's Ferry to Fernbank were converted to 5'-2 1/2"

gauge and operated by the Cincinnati Street Railway until 1940

[actually 1941]. The lightweight cars were sold to the Sand

Springs Railway at Tulsa, Oklahoma. (From: Hilton, George W. and

John F. Due, The Electric Interurban Railways in America.

Stanford University Press, 1960)

The life of many interurbans can look

relatively straightforward when distilled into a single

paragraph. Some smaller companies, such as the Lebanon &

Franklin or the Springfield & Xenia, did have

relatively simple and uneventful lives. Their financing,

construction, and operational history may be of little note to

anyone besides local historians or electric railway

enthusiasts. These companies operated on the same route from

start to finish, made no changes to power facilities, and ran

their original equipment to the end. The Cincinnati, Lawrenceburg

& Aurora was not that sort of company. It was so fraught with

poor planning, operational difficulties, and bad luck over its

30-year life that nearly a third of its track was rerouted at one

point or another, and the majority of that happened only within

the first three years of operation. They were an innovator in

economizing operations when the industry started to falter, and

they experimented with novel freight hauling operations. None

of these developments could have been foreseen when the CL&A

was first incorporated on October 24, 1898 under president John C.

Hooven, George H. Helvey, G. A. Rentchler, C. E. Hooven, and Fred

D. Shafer.

In the early planning stages, a prospective interurban company

would look for the easiest and least expensive route to serve as

many customers as possible. Unlike steam railroads which

need shallow grades, gentle curves, and room to accommodate long

trains, interurbans could work with steeper hills, tighter curves,

and very short passing sidings. The local nature of their

business meant they could not afford extravagances like tunnels,

major hill cuts, long bridges, or extensive fills and

trestles. Operating over public highways and bridges also

afforded significant capital savings, despite the operational

constraints imposed by such arrangements.

|

|

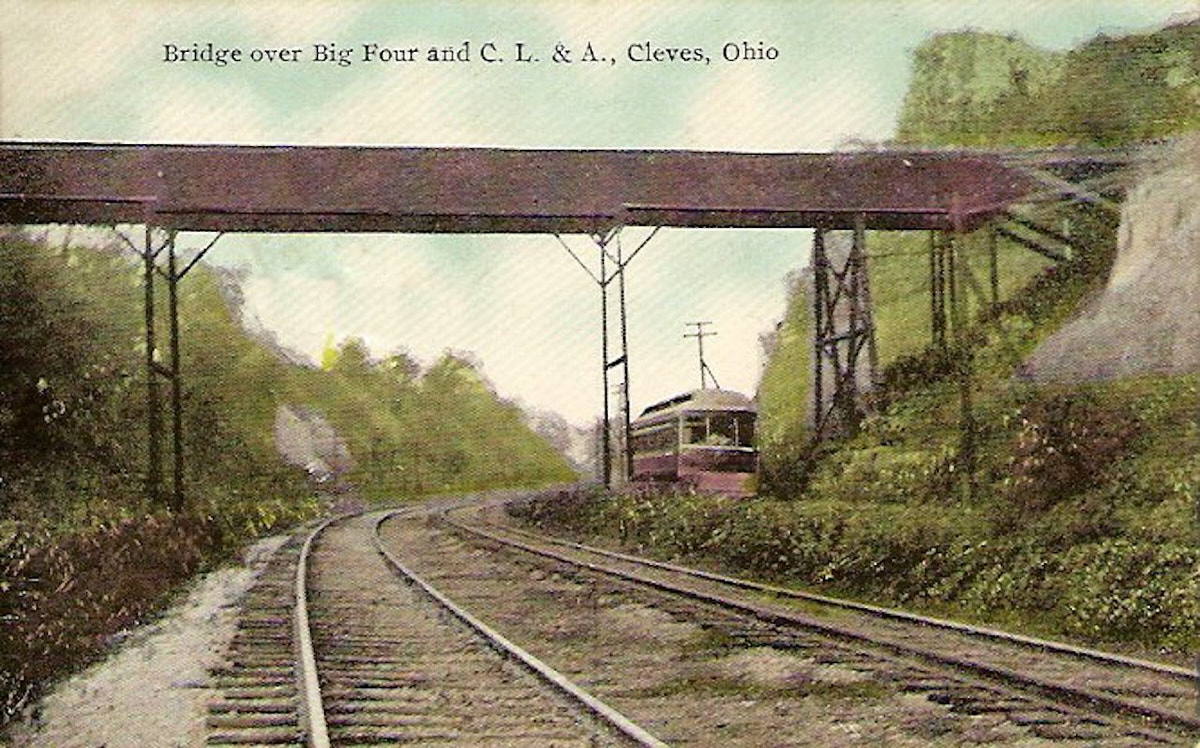

A CL&A car is crossing the

Great Miami River on the ca. 1884 highway bridge. The

single-track Big Four Railroad's bridge is visible to

the right, which reused the supports from the Cincinnati

& Whitewater Canal aqueduct from the late 1830s or

early 1840s. Both of these bridges were destroyed

by the flood of 1913, which washed away every bridge

over the Great Miami between the Ohio River and Dayton.

The horse and wagon are on Valley Junction Road, which

sits on a part of the canal the railroad elected not to

use.

|

For the CL&A, the major obstacles between

Anderson Ferry and points west were the Great Miami River and its

floodplain, as well as the narrow North Bend Hill that separates

the Ohio and Great Miami valleys. Running exclusively along

the flat Ohio River valley directly to Lawrenceburg was not ideal

since it would bypass populated areas, and it would also require a

long bridge and extensive earthworks and trestles to cross the

meandering mouth of the Great Miami. Deviating from the Ohio Valley however

required crossing the short but steep North Bend Hill to Cleves

before striking out to the west. Company planners determined

that North Bend Hill was the lesser of two evils.

While a continuous route along the Ohio River to Louisville was a

laudable goal, it was well beyond the reach of the company.

Rising Sun was the initial planned terminus, however Aurora and

the Dearborn County Commissioners refused to grant permission to

cross the George Street Bridge over Hogan Creek, declaring the

iron bridge unable to handle the additional weight. Materials

which had already been ordered for that route, including one block

of track already laid on Main Street to 2nd Street, were torn up

and redirected to a branch line to Harrison instead. This

branch line required navigating North Bend Hill, crossing the

Great Miami, and following the Big Four Railroad and their Whitewater Division and

Kilby Road to the north. So what was the best way across the

river?

The original highway between Cleves and Hooven on the west bank of

the Great Miami River was today's State Road/Henderson Kupfer

Drive. An old wooden truss bridge, which may have dated to as

early as the 1830s, crossed the river near today's BMX bike track

in Gulf Community Park. After that bridge was washed out by the

flood of 1883, a new steel truss bridge was built upriver just to

the north of the Big Four Railroad bridge. These

two bridges were on somewhat higher ground than the old State Road

crossing. The CL&A obtained a franchise to cross this highway

bridge for their branch line to Harrison.

So how would the main line get from Cleves and North Bend to

Lawrenceburg and Aurora? There was no direct highway between

Cleves and Elizabethtown to the west near the state border, so if

they decided to extend their main line past Valley Junction at

Kilby Road, the CL&A would need to purchase a right-of-way,

cross the Big Four Whitewater Division tracks, build an extensive fill or

trestle to stay above the floodplain of the Whitewater River, and

build a bridge over the Whitewater itself. Instead, they elected

to build a short trestle over the Big Four near the border of

Cleves and North Bend, at what was deemed Cleves Junction, then

follow what is today Miamiview Road to Lawrenceburg Road and the

Lost Bridge to Elizabethtown. The Lost Bridge was a covered

wooden Howe truss on stone piers that was built in 1866. It

got its name because the original construction contract did not

include the earthen fill on the Elizabethtown side of the river,

so it was rendered useless and thus "lost" until nearby farmers

filled the approach themselves. The name may also stem from

its rather isolated location and lack of traffic even today,

leading to some stories of wayward surveyors and county assessors

unable to locate the bridge to inspect it. Nonetheless, this

bridge allowed the CL&A to cross the Great Miami and also

avoid the Whitewater, whose confluence with the Great Miami is

about a half mile upstream. The tracks then followed the old

Louisville Pike, now US-50, Oberting Road, and Ridge Avenue to

Lawrenceburg.

Arrival in Lawrenceburg was no simple feat

either, however. The route via Ridge Avenue allowed the

company to serve the community of Greendale and its distilleries

while avoiding the low-lying and sparsely populated floodplain to

the east. It also meant that the route nearly bypassed

Lawrenceburg, since Ridge comes in northwest of town and the road

to Aurora turns off prior to entering Lawrenceburg. So a

spur track had to be built to Walnut Street in order to reach the

center of town, requiring cars to backtrack nearly a mile on the

way to or from Aurora. This is similar to the IR&T Suburban Traction

spur track in Mt. Washington, though much longer. The

in-and-out movement took 12 minutes, greatly irritating through

passengers.

Operations began on April 12, 1900 between Anderson Ferry and the

carbarn in North Bend. The opening of the CL&A greatly

improved access to the city for Cincinnati's most remote

neighborhoods. Delhi, Sayler Park (Home City before it was

annexed), and Fernbank all grew up as railroad commuter suburbs in

the late 19th century in proximity to bustling industry along the

Ohio River and both the Big Four and B&O railroads. When the CL&A was

built it added yet another set of tracks through this narrow

linear corridor hemmed in by the river and steep hillsides.

Towns farther out also benefited from more frequent service and

lower fares than were available on the older steam railroads. Two

weeks after opening, operations were extended west of the carbarn

to Cleves, and the cars reached Lawrenceburg on June 1. The

tracks to Aurora were also complete, except for the bridge over

Tanner's Creek on the west side of Lawrenceburg. A car was

shipped across the creek by the B&O Railroad, and it operated as

a shuttle from Aurora starting on June 4. Passengers would

have to walk over the old wagon bridge to waiting cars until the

CL&A's own bridge was completed. The Harrison branch was

opened on July 4, 1900 to much fanfare.

|

|

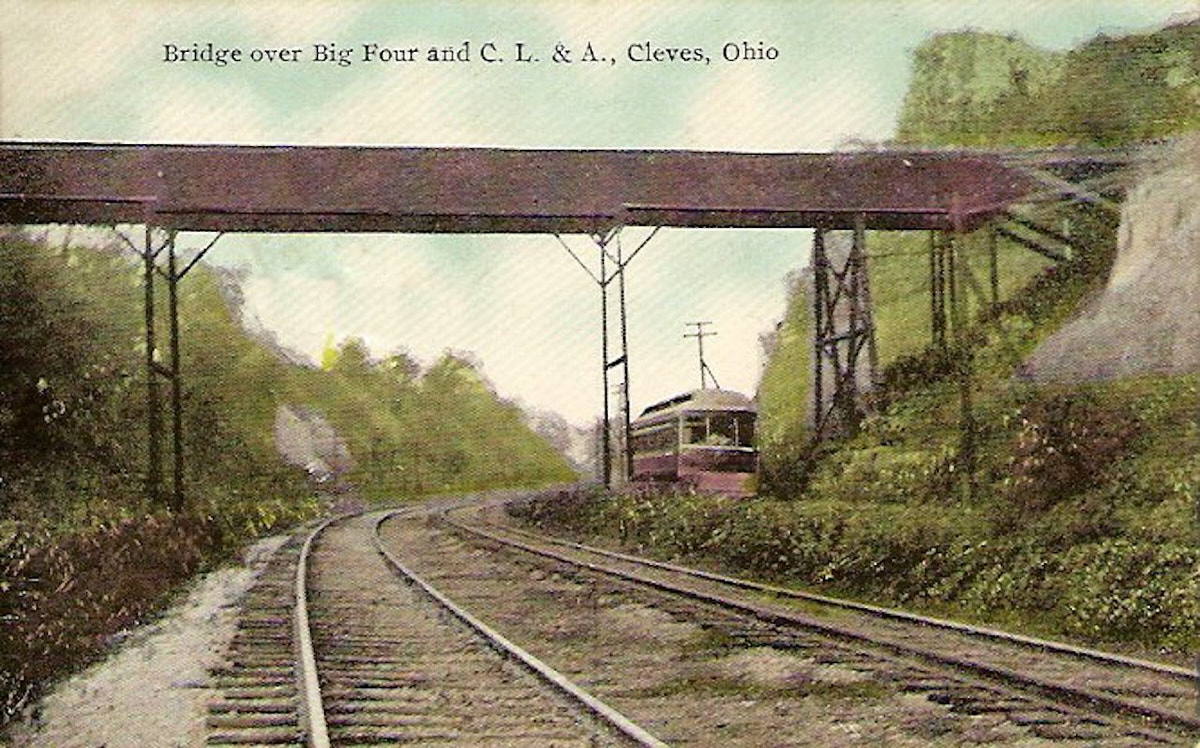

A CL&A car shares the cut

through North Bend Hill with the Big Four Railroad. This

cut was originally constructed in 1888 for the Big Four

to bypass the old Cincinnati & Whitewater Canal

Tunnel to the east. It was widened in 1903 to allow the

CL&A to relocate off of Miami Avenue, and again in

1959 to relocate US-50 off of Miami Avenue. The Harrison

Avenue bridge that once connected to Cliff Road is

overhead. It was demolished as part of the US-50 project

in favor of a new overpass at Brower Road to the south.

|

Construction was typical for the Cincinnati

area, with double track from Anderson Ferry west to the edge of

Fernbank, where it became single track. Rails were generally to

one side of the highway in rural areas, and in the middle of the

street in towns. Due to operating mostly on level ground and

avoiding rivers as much as possible, there were few major cuts,

fills, or trestles. The terminal area at Anderson Ferry is quite

far removed from downtown Cincinnati, however, so a long 40 minute

streetcar ride was necessary to reach Fountain Square. Since the

company elected to use standard gauge cars, they had no way to

extend service closer to downtown over the incompatible street

railway tracks. This was an interesting choice because for the

first 20 years of operations, the CL&A offered no freight

service whatsoever, and they didn't interchange cars with steam

railroads. Had they used broad gauge tracks, they would at least

have had the opportunity to run their passenger cars to downtown

over the street railway. At the time the CL&A was

constructed however, the powers that be at the Cincinnati Traction

Company did not want interurbans running over their tracks,

preferring to set up transfer locations at the end of the

streetcar lines.

The power station and carbarns were located on the east side of

North Bend on River Road, a little ways east of Ohio Avenue/St.

Annes Drive, almost at the exact center of the system and with

easy access to various coal depots. Nevertheless, the total length

of the system was at the limits of transmission distance for 600

volt DC power, and several additional feeder wires were needed to

maintain adequate power at Anderson Ferry, Aurora, and

Harrison. Since the electrical system was barely adequate to

begin with, no retail power was sold to customers along the way,

unlike some other companies who did so to diversify their

revenues. Eight 44-passenger double-ended cars equipped with four

motors on 33-inch wheels were the initial equipment roster. These

cars weighed 25-26 tons each and were geared for 35 mph free

running. A 1907 census report of street and electric railways

mentioned 12 passenger cars and one sweeper car on the

roster.

Soon after operations began on the CL&A, some specific

operational challenges became apparent. As early as 1901 it

was clear that the Lost Bridge was a liability due to settling of

some of the piers and abutments, and cracks developing in

structural members due to the weight of heavy interurban

cars. In August, 1901 the CL&A reported that they were

going to abandon use of the bridge, though if they planned to

simply build their own bridge or relocate the entire Miamiview

route is unclear. For the time being they took no action on

this plan.

A few steep grades were also notable issues. Despite the

relatively level river valleys where the CL&A ran, proximity

to hillsides and riverbanks still led to a couple of sub-par

routings. The first one was at the north end of the trestle

over Muddy Creek, at the border between Fernbank and

Addyston. Almost immediately after turning off of Gracely

Drive at Birch Lane and becoming single-track, the tracks then

passed over a 900 foot trestle on the way to Main Street in

Addyston. At the end of the trestle there was short but very

steep 30 foot climb to the level of Main Street at what is today

the Harbor View Apartments. This grade proved to be a

hazard, and President Hooven petitioned Addyston to allow them to

relocate their tracks off of Main to a private right-of-way behind

the homes on that street at the same elevation as the

trestle. The approval was granted by Village Ordinance 227

on or about October 21, 1902, and the new route was put under

construction to West Fork Muddy Creek at 1st Street and Dinning

Lane where the CL&A rejoined Main Street.

The Muddy Creek grade paled in comparison to North Bend Hill,

which was a significant operational handicap for the company. One

of the steepest grades of any streetcar or interurban serving

Cincinnati, traversing the 10% slope between Brower Road and

Harrison Avenue used a great deal of power, and slipping or

runaway cars were serious safety concerns. Despite the

objections of some vocal residents who would lose direct access to

the tracks from their homes, the company obtained permission in

1903 to use the Big Four’s cut through North Bend Hill, first

constructed in 1888 to bypass the former Cincinnati &

Whitewater Canal tunnel which the railroad had repurposed for

their own use. The CL&A tracks diverged from the old

River Road at Symmes Avenue, and they rejoined the previous route

on Miami Avenue at Mt. Nebo after the cut was widened to

accommodate the additional track.

That same year, the Lost Bridge burned down,

cutting the main line in half. The fire that destroyed the

bridge in the early morning of July 28, 1903 accelerated the plans

the CL&A had been dragging their feet on over the prior two

years. The company was able to strike up another bargain with the

adjacent Big Four Railroad, which allowed them to build an

extension from Kilby Road at Valley Junction to Elizabethtown on

the railroad’s right-of-way, even sharing their bridge over the

Whitewater River with the use of a gauntlet track. The Miamiview route

was torn up, and the rails were likely reused to build the new

connection. Cleves Junction was then removed, and Valley Junction

(sometimes called Harrison Junction to differentiate it from the

Big Four's junction of the same name) became the new branching

point. Track in the highway between OH-128 and Valley Junction was

relocated to a private right-of-way as well.

|

|

Remnants of the CL&A power

house after a massive explosion in 1915. Note the car

and tracks to the left, and the Ohio River in the

background.

|

After the troubles of 1903, the CL&A

settled into a fairly steady operation. Ridership was

average for the Cincinnati area, with 1.5 million passengers in

1912. That said, the C&LE

and Cincinnati & Hamilton

interurbans were by far the strongest in the Cincinnati Area,

serving more than 4.3 million passengers each, so the CL&A

actually took third place in ridership out of nine main routes

spread among seven companies. The populated outer

neighborhoods, heavy industrial employment, and several towns in

relatively close proximity boosted passenger numbers. The branched

nature of the system allowed the company to operate cars on a 30

minute schedule between Anderson Ferry and Cleves, with

alternating cars providing hourly service to Aurora and Harrison.

Despite the amicable relationship with the Big Four, the

CL&A did eventually have to move the Valley Junction -

Elizabethtown route onto its own right-of-way and also build their

own bridge over the Whitewater River, though when that was done is

unclear.

It appears that shortly after CL&A began operations, the

adjacent Big Four saw them not as a competitor, but an opportunity

to dispose of their own commuter operations. While long-distance

passenger service remained profitable for mainline steam railroads

for decades, the short-haul, peaky, and uni-directional nature of

daily commuter operations were a hassle to serve at best and

unprofitable at worst. They were, however, never able to

completely shed this service until after the CL&A was

abandoned and Union Terminal opened in 1932. All passenger

trains were required to use the new station, but it was

unacceptably far from downtown for commuters, and most if not all

railroad commuter operations ceased upon its dedication.

Prior to that time however, the wider station spacing and more

convenient terminal location at 3rd Street and Central Avenue made

trips to downtown faster on the Big Four, though they had few

off-peak trains and higher fares than the traction line.

Nonetheless, they still went out of their way to accommodate the

CL&A, defying the usually hostile practices of most mainline

steam railroads east of the Mississippi River, perhaps also

because the CL&A offered no freight competition.

A benefit of the company's original route

along Miamiview would become sorely apparent after the devastating

flood of 1913. Every bridge over the Great Miami River from Dayton

south was destroyed, along with the CL&A and Big Four bridges

over the Whitewater River. Much of the Harrison

branch was inundated or washed out as well since it closely

followed the Whitewater River. The CL&A could only operate from Anderson

Ferry to Cleves while extensive repair work and new bridges were

constructed. Temporary wooden pile structures were built to keep

the railroads and highways open while permanent spans were built.

The expenses and lack of revenue caused a loss of $100,000 and

President Hooven petitioned for receivership under Frank B. Shutts

of Miami, Florida. Had the Lost Bridge not burned down in 1903, or

the County had been more expedient in replacing it (its successor

wasn't opened until 1906, and every time this bridge was destroyed

or closed in 1903, 1913, and 1980 there were arguments over

whether it would be replaced at all), the CL&A would likely

have been able to restore operations to Lawrenceburg and Aurora

much sooner. The Miamiview route is above flood level, and only

the half mile of road west of the Lost Bridge on the floodplain

between there and Elizabethtown would have needed rebuilding.

Unfortunately that ship had sailed ten years prior. After

full operations were restored, Shutts resigned as receiver on

December 28, 1914, then Edward Stark was appointed and assisted by

Hooven, who was appointed January 17, 1918.

Still reeling from the 1913 flood, the

company's power station exploded in 1915. The resulting fire

leveled nearly the entire building, which also included the

carbarn and shops. The structure was rebuilt, and some second-hand

cars were purchased from the Chicago & West Towns Railway to

replace those lost in the blaze. By 1917 the company was

purchasing power from Union Gas & Electric, with 33 kV 3-phase

AC power feeding new 200 kW automatic substations with rotary AC

to DC converters. One substation was somewhere in Fernbank, and

the other was next to US-50 just east of the Ohio/Indiana border,

and it is still standing as of August, 2021. How power was

supplied in the intervening two years is unclear, but it does seem

that they rebuilt the power station even if only used for two

years. Either way, the carbarn and shops remained at that location

after reconstruction, and it was used until 1937 as a garage by

the Ohio Department of Highways after the CL&A closed down.

The building sat derelict until 1959 when it was demolished to

widen US-50.

The year 1918 comes up regularly throughout reports of the

interurban industry as being particularly difficult, where many

companies entered receivership or began talks of abandonment.

Price and wage inflation, virtually unheard of before WWI, ate

into revenues since fares were fixed by franchise agreements that

never anticipated an inflationary monetary system or a major world

war. Maintenance costs for aging infrastructure and equipment was

also rising along with greater competition from automobiles,

buses, and trucks. There were really only two choices that

traction lines had: abandon or modernize. Still deep in

receivership from the 1913 flood and power station explosion, the

CL&A chose to modernize in an attempt to restore the company

to profitability and pay down their debts. Since the power system

had already been upgraded, the next step was purchasing new

lightweight one-man cars. These vehicles from the Cincinnati Car

Company were half the weight of their old ones, weighing only 12.5

tons and having 24-inch wheels, which were quite small for

interurban cars at the time. This allowed for level boarding at

platforms and fewer steps up from the street. Since they were half

the weight, they also used half as much power, they didn’t beat up

the tracks as hard as heavier cars, fewer rail ties were needed,

and the cars required less maintenance. They also eliminated the

need for a conductor, saving on salaries, although a second

crewman was still carried between Lawrenceburg and Aurora to flag

at-grade railroad crossings of the B&O in Lawrenceburg at

Walnut and Williams Streets, 3rd Street, and at George Street in

Aurora. By reducing the number of stops, eliminating some street

running, and tightening up layover times at Aurora and Harrison,

they were also able to maintain their running schedule with five

active cars instead of the original six, with two cars kept in

reserve. This move was so successful at reducing operating costs

that other roads in Cincinnati and around the country began

similar programs to modernize.

|

|

The CL&A was a pioneer in

purchasing new lightweight one-man cars. This particular

one was manufactured by the Cincinnati Car Company,

which also incorporated many of the same techniques into

more modern streetcars. The color scheme for these appears to

have been Pullman green above and below the windows,

cream around the windows with maroon window sashes

and doors, and a gray roof.

|

While the CL&A operated through a highly

industrialized corridor, freight business was nonexistent as

mentioned previously. Industry reports in the mid 1910s show 100%

of company revenue coming from passenger service. Interestingly, a

booklet called Along the Line, published shortly after operations

began, noted the strong farming community at Elizabethtown and

other smaller manufactories along the way that appeared to be good

potential freight customers. That said, the B&O, Big Four, and

river barges were already serving online customers with their own

freight sidings and spur tracks. The milk, fruit, canned goods,

and

smaller shipments that were a mainstay of the industry were likely

also spoken for by the larger railroad companies who could deliver

those goods to downtown Cincinnati in one movement. This lack of a

connection to the downtown Cincinnati market was also cited in one

report as a reason for the CL&A's lack of freight business.

Even if broad gauge cars had been used, the company would likely have

been

limited by the street railway company in the type of freight

services they could provide over their tracks, if any. The whole

reason the street railway used broad gauge tracks in the first

place was to prevent freight trains from running through city

streets after all.

Despite all those obstacles, in an effort to diversify their

revenues, the CL&A became a pioneer in container shipping by

partnering with the Cincinnati Motor Terminals Company. This

company was born out of the freight hauling paralysis of WWI when

railroads, already operating near their maximum capacity, were

strained to the breaking point from the shift to wartime

operations. Cincinnati was a notorious bottleneck in the nation's

railroad system even before the war, with less-than-carload (LCL)

freight taking multiple days to be transferred between railroads

or to customers in the city. These sorts of small loads, made up

of many different types of freight from different customers all

bound for different destinations were a logistics nightmare, and

handling them through excessive local rail switching operations or

teams of horses pulling trailers made them ridiculously slow and

expensive. All this was on top of a massive freight car shortage

caused by the war, while many routes were completely shaken up by

the change in traffic patterns to delivering war materials to the

east coast for ocean shipping to Europe.

The Cincinnati Motor Terminals Company founder, Benjamin Franklin

Fitch, designed detachable trailer bodies for trucks which allowed

them to be loaded at freight depots as parcels came in, while the

driver could be out picking up or delivering other containers that

were full. Previous trucks and horse-drawn trailers were all one

unit, requiring the driver to wait for it to be fully loaded or

unloaded. Initially delivering only between the various steam

railroad terminals in downtown Cincinnati, this company was able

to move more than ten times the tonnage of the older trap cars

(similar to boxcars) used by the Railroads for LCL hauling. In an

effort to introduce more intermodal shipping, where the containers

could be loaded and moved via not just truck but also train, the

CL&A was approached in 1921 to install hoists and loading

facilities at Anderson Ferry so full containers could be delivered

by truck and then offloaded as necessary along the way to Indiana,

or vice versa. One of the old Chicago & West Towns cars was

modified to remove the body and create a flat platform for two of

the containers, leaving motorman's cabs intact at the front and

back. A small single-truck flatcar was also outfitted to carry a

single container. A few other local railroads dabbled in this type

of operation, such as the C&LE

which also built hoists and had some of their own flatcars that

could carry two containers. Fitch did not have much luck

introducing his trailers to other cities, though he did eventually

have success courting both the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York

Central Railroad. The Great Depression however would take its

toll. Reduced tonnage meant fewer logistics problems, while the

PRR and NYC both implemented their own trucking services and

canceled their contracts. The C&LE stopped hauling trailers in

1935, and in 1937 the Interstate Commerce Commission determined

that rail freight containers for this sort of operation had to be

owned by the shipper, not the railroad, which basically killed it

as a going concern. Motor trucks in general took over LCL freight

hauling all on their own, eliminating the railroads from the

picture. Only since the end of the 20th century has intermodal

cargo shipping really come back, with today's distinctive metal

containers being shipped across the oceans for transloading to

railroad or truck.

Another economizing move made by the CL&A

and other interurbans was to eliminate redundant trackage and shed

street maintenance liabilities. Like the IR&T lines and CM&B coming into the

east side of Cincinnati, the CL&A had several miles of

double-track within the city limits and on public streets. In the

case of the IR&T Rapid Railway line, a few miles were

purchased by the street railway company while they were still in

operation, but in most other cases the increase in traffic that

would warrant double track operation never materialized, nor did

the hoped-for buyout by the street railway, which more often only

happened at abandonment. The CL&A thus eliminated all of their

double track, which was only within the city limits in the first

place, and they replaced it with a single track with passing

sidings. They also moved the route through Delhi, Sayler Park, and

Fernbank off of Gracely Drive (then known as Lower River Road) to

a private right-of-way next to the Big Four railroad tracks, much

like it was originally constructed east of Delhi. The new tracks

had to bend around the small railroad commuter stations in these

neighborhoods, and it ultimately swung north and east to meet up

with Birch Lane where it rejoined the existing route into Addyston

and beyond. This track realignment reduced increasingly frequent

altercations with automobiles and motor trucks on Gracely, which

was the main road through those neighborhoods prior to the

relocation and upgrading of River Road to a highway in the 1950s

and 1960s, while also absolving the company of responsibility to

maintain the roadway around their tracks. By the 1920s

municipalities were pressuring interurbans to pave the street

around their rails, if not from curb to curb, which was well

beyond the scope of their original franchises, and it would only

benefit competing automobile, truck, and bus traffic, while

complicating track maintenance. A similar move was made in

Cleves in 1923, eliminating the remaining street running on Miami

and Cooper, and utilizing a right-of-way next to the Big Four to

the highway bridge over the Great Miami, thus eliminating the

tight turns at Mt. Nebo. Addyston apparently ordered the

company to remove their tracks from Main Street at some point,

because of failure to maintain the street to the village's

satisfaction or pay franchise fees, but it's unclear if this was

ever carried out.

|

|

The CL&A terminal at Anderson

Ferry Road in approximately 1921, showing Cincinnati

Motor Terminals trailers being hoisted onto a truck, and

the modified car which could haul two such trailers.

From "On the Right Track: Some Historic Cincinnati

Railroads" by John H. White, Jr.

|

While the economizing moves and introduction of

freight handling helped the company's finances immensely,

operating across state lines and through several municipalities

made raising fares in the face of price and wage inflation more

difficult than for other companies. Extension to downtown to

allow either one-seat passenger service to Dixie Terminal, or to

connect with the Cincinnati subway that was under construction in

the early 1920s was well out of financial reach of the

CL&A. The West End Rapid Transit Company was chartered

as early as 1915 to build this connection, including a mile-long

viaduct over the Mill Creek Valley to span the tangle of railroads

beneath. Private financing dried up during World War I and

in 1920 the Rapid Transit Commission rejected a petition to put a

$1 million public bond issue for the project on the ballot,

leaving the CL&A stranded at Anderson Ferry for the remainder

of its independent life.

By the late 1920s the benefits of modernization had worn off, and

the company's fortunes were looking bleak. A report was

prepared in 1927 for the Cincinnati Street Railway in

consideration of purchasing the company. They recommended

the Harrison branch be abandoned immediately for hemorrhaging

money, since it was serving barely 100 passengers per day.

Monthly operating expenses of the branch line were $2,152.00, more

than five times the revenue of $417.85 from passenger fares.

The CL&A had purchased a bus company that operated between

Fountain Square, Anderson Ferry, and Fernbank in an effort to

control competition, but operating this bus line was at a loss,

and the street railway report suggested only retaining the bus

service between Fountain Square and Anderson Ferry. The

street railway company was not interested in buying out the

CL&A and in 1928 the company was reorganized as the Cincinnati Lawrenceburg & Aurora Electric

Railway Company, closing out their 15 year receivership.

Charles H. Deppe, vice-president of the Fifth-Third Union Trust

Company was the receiver, and he was slated to become president

of the reorganized company along with Joseph L. Lackner of the

law firm Maxwell & Ramsay who would become secretary.

Samuel I. Lipp would continue as vice-president and general

counsel having been elected prior to this date.

At some point shortly thereafter the CL&A was

purchased or taken over by Lawrence Van Ness, who was primarily

interested in the company's electrical infrastructure, which could

be sold off to growing power companies. He was on the board

of directors according to a 1921 financial report, but his

involvement before the 1928 reorganization is unclear.

Regardless, the eventual closing of the road and takeover by the

Cincinnati Street Railway after final abandonment on November 30,

1930 is similar to what happened with the CM&B on the east

side of town, which was also purchased by Van Ness. The street

railway company originally planned to substitute the service with

buses, but residents along the line wanted to retain rail service.

So the infrastructure was purchased at scrap value for streetcar

use. The track gauge had to be converted from standard to broad,

which was done by leaving one rail and moving the other one out

six inches to the new spacing. Since nearly the entire route was

on private right-of-way since 1918 they didn't have to tear up

streets to modify the tracks. The line was cut back to Birch Lane,

just off of Gracely Drive where it originally went to single

track, and a loop and small electrical substation were installed.

The new route 30 Fernbank opened on January 1, 1931. Since the

standard gauge cars were of no use, but were still in good shape,

they were sold in 1932 to the Sand Springs

Railway in Oklahoma, which was a latecomer to the interurban

scene, opening in 1911 between Tulsa and Sand Springs. Streetcar service on route 30 was replaced with buses

on June 1, 1941 and the tracks were pulled up for wartime scrap.

CL&A car 918, renumbered 68 by its new

owner, survived until 1955 when Sand Springs converted to diesel

freight operations. That car was obtained by the Illinois

Railway Museum in 1967 and has been restored to its state in the

1950s under Sand Springs, with a bright yellow body,

cream windows, and maroon on the roof and doors. The rest of the

cars purchased by Sand Springs from the CL&A were

apparently scrapped in 1955 or before.

The CL&A terminal at Anderson Ferry

originally met a large streetcar loop with an extra layover track

next to the traction line's depot. The odd frontage street to the

north is where the original River Road and streetcar line ran

before bending slightly south. The CL&A terminal was actually

east of Anderson Ferry Road, but straightening out the road's

alignment paved over the station location in 1948. This sort

of connection was the preference of the Cincinnati Traction

Company, which did not want interurbans running over their tracks

until political pressure or a change in management a bit later

into the first decade of the 1900s. Pretty much all traces of the

CL&A's route within the city were obliterated by the widening

and realignment of River Road in the 1950s. The original double

track route within the city limits basically followed the south

side of the old narrow River Road west from here to Delhi, with

the outbound track on the street and the inbound track off to the

side near the railroad tracks. The rail in the street was removed

when the line was single-tracked in 1918. Upon reaching Delhi, the

line originally merged with Gracely Drive to pass through the

neighborhoods of Sayler Park and Fernbank. After 1918, the tracks

in the street were removed and the whole line paralleled the Big

Four railroad and the now-gone Nokomis Avenue until about 500 feet

past Thornton Avenue where it turned to meet up with the original

route at Birch and Gracely. Birch Lane is mostly unimproved

gravel, but the curbs on Gracely form corners to what was

apparently intended to be a decent sized street.

|

|

The CL&A Cleves Junction

station was only used for three years before the tracks

were rerouted. Miami Avenue is to the left, and to

the right the ground drops off precipitously to the Big

Four railroad cut. The plank sidewalk at the

bottom right is the start of a trestle that crossed the

cut. The building was completely dilapidated by

the 1990s and it was subsequently demolished.

|

The interurban line then ran on its own

right-of-way for a short distance, crossing Muddy Creek on its own

trestle. Originally it took a short but steep uphill to Main

Street from the trestle at what is today the Harbor View

Apartments, but after 1902 it turned to the west at the end of the

trestle and ran behind the houses on Main Street. Graded

right-of-way remains behind those houses before coming onto Main

Street in Addyston at Dining Lane where bridge piers and abutments

remain over the small west fork of Muddy Creek. The CL&A

continued on Main Street through Addyston, then US-50 west of

Bowman Lane. The site of the power house and carbarn was mostly

obliterated by widening of US-50 but it was located in a grove of

trees east of Ohio Avenue/St. Annes Drive, below Sunset Avenue.

Before US-50 was widened and bypassed North Bend to the west, the

highway turned directly onto Miami Avenue, as did the CL&A

from 1900-1903. Cleves Junction was located at 325 Miami Avenue

near Wamsley Avenue, with a small station building and the tracks

to Aurora turning off Miami on the north side of the station.

Tracing the short-lived Miamiview route between Cleves, the Lost

Bridge, and Elizabethtown has proven enormously difficult due to

its short lifetime. Since parts of the CL&A that ran for its

full 30 years are still difficult to spot, trying to find roadbed

that was only used for three years is a significant

challenge. There are no maps and no property records that

indicate the location of this route save for a few descriptions

and poorly captioned photos from the company's Along the Line

booklet. This booklet shows the underpass at Elizabethtown, and

also a photo of private right-of-way just east of “Harold Switch”

which was a passing siding a little ways east of the confluence of

the Great Miami and Whitewater River. A newspaper clipping

from November 1900 notes a head-on collision between two CL&A

cars when one motorman mistakenly went through Harold Switch

without meeting the approaching car due to a misunderstanding of a

schedule change. The collision was apparently in front of

the home of one Dr. Smedley, but that location is also a

mystery. Either way, that was definitely on a private

right-of-way, and the photo looks to be a bit up the hill

too. Regardless, there doesn't seem to be any evidence in

topographic maps, but wooded hillsides tend not to be well

documented in that respect. Earl Clark Jr's research on the route

also suggests a private right-of-way to the south of Miamiview

near the toe of the hill. In the meantime, that's how the

route is mapped, though with many question marks as to its true

disposition.

Back at North Bend, after 1903 the CL&A

diverged from the highway at Symmes Avenue and shared the newly

widened cut through the hillside with the Big Four Railroad past

Harrison's Tomb. The eastbound/southbound lanes of today's US-50

are on the old roadbed after significant widening of the cut was

done to accommodate the highway. The CL&A after 1903 turned

back to Miami via Mt. Nebo and proceeded north through Cleves to

Cooper. It then came back onto US-50 and crossed the Great Miami

River, sharing the old highway bridges. After the 1923 Cleves

bypass was built, the tracks simply continued north past Mt. Nebo

where US-50 runs today. The route to Aurora followed US-50 into

Indiana and Lawrenceburg. Detailed USGS maps of southeast Indiana

from the CL&A operating period have been nearly impossible to

locate, so the routing from the state line through Greendale

should be taken with a grain of salt. Proximity to the Big

Four Railroad and the old Whitewater Canal next to Oberting Road

makes figuring out what was what rather difficult. The CL&A

crossed the Big Four's Greendale cutoff on a short bridge roughly

100 feet east of the current Ridge Avenue overpass in what was

originally a small village called Homestead that was later annexed

to Greendale. The CL&A then ran slightly to the east of

Ridge and came onto the road somewhere around Probasco Street. As

mentioned earlier, the street running in Lawrenceburg was somewhat

bizarre due to the layout of the roads coming into town. There was

a T-intersection at 3rd and Main with a spur into town from 3rd to

Walnut to High Street that required the motorman to change car

ends for the return trip. After crossing Tanner's Creek, Doughty

Lane behind the Family Dollar is the old route. The remainder of

the line to Aurora was on a private right-of-way next to the

highway. It turned onto George Street and ended just short

of the bridge over Hogan Creek in Aurora.

The branch line to Harrison basically

paralleled the Big Four's Whitewater Division, now I&O, along

Kilby Road. North of the I-275 exit Kilby Road jogs from the west

side of the Big Four to the east side, and immediately thereafter

it crosses Dry Fork Creek directly on the CL&A's old

alignment. North of that point there's a bit more space between

today's road and the I&O where the CL&A ran, though it's

just overgrown trees now. There appears to be some extant

right-of-way next to the I&O after Kilby diverges on a due

north tangent away from the railroad, but it's all on private

property with no cross streets. At Campbell Road west of

Kilby was the old Simonson station. After abandonment,

Clarence Roudebush, nephew of Benjamin J. Simonson, a local farmer

for whom the station was named, moved the small wooden station

building to use for storage on his own farm. Around 1980, his

Grandson, Frank A. Roudebush, decided it should be saved and he moved

the Simonson Station to Ann and Gene Woelfels yard at 6590 Kilby

Road. It was restored in 2014-2015 by the Harrison Rotary

Club by request of the Harrison Village Historical Society.

West of Simonson the traction line followed the south side of

Campbell until reaching State Road, running up the east side of

the road until reaching town, then moving to the middle of the

street at the heart of Harrison, where passengers could disembark

to either Ohio or Indiana depending on which side of the car they

exited.

Main

Line Photographs from Anderson Ferry to Aurora

Harrison Branch Photographs from

Valley Junction to Harrison

Return to Index