An early horsecar, also showing the muddy condition of the streets at the time.

Introduction

The history of Cincinnati and northern Kentucky's transit systems

illustrates how a city and its environs evolved over time as new

transportation technologies were introduced, refined, and ultimately

supplanted. In the 1850s, Cincinnati was the 6th largest city in the

USA with a population of 115,000, just slightly beaten out by New

Orleans, and not much smaller than Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore.

Chicago was barely on the map at the time, and Cleveland and Columbus

were little more than large towns with populations under 20,000. In the

mid 19th century, Cincinnati's population was concentrated in today's

downtown, Over-the-Rhine, and parts of the West End. The Mill Creek

Valley was a sparsely settled area of small farms, orchards, and

vineyards, as were many of the hilltop communities. With so many people in an area of only a few square miles, the population

density at the time was the highest in the country. Even Manhattan

didn't surpass the population density of Cincinnati's core neighborhoods

until 1900. The barriers of the Ohio River to the south, steep

hillsides to the north and east, and the swampy, often flooded, Mill

Creek Valley to the west prevented much outward development. Needless

to say, it was so crowded that people were desperate to

move into other areas.

Horsecars and Early Companies

The omnibus was the first attempt at any meaningful public

transportation. It was, however, little more than a glorified

stagecoach. Since most of the streets were dirt, in anything but

perfect conditions the omnibuses were so slow and unreliable that it was

faster to just walk. It wasn't until steel rails were perfected in

the late 1850s that the situation started to improve. With relatively smooth

rails, a carriage with steel wheels could be pulled by a team of horses

or mules much more easily than the previous omnibuses. Starting on

September 14, 1859, horsecar lines began to spread out from downtown to

the east, west, and northwest. That first line was opened by the

Cincinnati Street Railroad Company (not to be confused with the later

Cincinnati Street Railway Company) from 4th and Walnut on a single-track

loop to the West End and back to downtown. At the time, just about

every horsecar line was operated by a

separate company. Some of those companies were, along with the

aforementioned Cincinnati Street Railroad Company, the City Passenger

Railroad Company, the Passenger Railroad Company of Cincinnati, the

Pendleton & 5th Street Market Space Street Passenger Railroad

Company, the Pendleton Street Railroad, and the Route Nine Street

Railroad Company.

|

An early horsecar, also showing the muddy condition of the streets at the time. |

The first horsecar line in Northern Kentucky, the Covington Street Railway Company, was incorporated in 1864 to run on Madison Avenue and across the new Suspension Bridge when it was completed. By the late 1870s horsecars stretched along Madison, Scott, 3rd, 4th, Main, and Pike in Covington, and a tangle of different tracks circled the blocks near the approach to the Suspension Bridge. These were split about evenly between the original Covington Street Railway and the South Covington & Cincinnati Street Railway Company. The Newport Street Railway also began operations in 1867 with a large loop between the riverfront and 11th Street via York and Washington. These horsecars used the 4th Street bridge over the Licking River to access the Suspension Bridge to Cincinnati. A more direct connection to Cincinnati was made in the late 1870s with the opening of the Newport & Cincinnati (L&N) Bridge. The Newport and Dayton Street Railway also operated a line along Front and Fairfield from the L&N Bridge east into Dayton. The early companies and operations of horsecar lines in Northern Kentucky were very similar to those in Cincinnati, but with the added complexity of dealing with many different municipalities, county governments, bridge companies, and interstate commerce laws.

In 1873 a handful of the Cincinnati lines were

brought under control of the Cincinnati Consolidated Railway, though

there were still several other companies operating. In 1879 new

legislation attempted to define and standardize many of the operational

procedures of these companies. It specified responsibility for

road maintenance, rules for operation, and performance requirements.

The year 1880 also saw the birth of the Cincinnati Street Railway

Company. The Cincinnati Consolidated Railway merged with a number of

other lines, mostly on the west side of the city, into the new company.

It was at this time that Cincinnati's peculiar rail gauge came into

being as well. There was a great deal of apprehension about letting the

steam railroads come into the central part of the city. The large

locomotives with fast spinning wheels, pistons, steam vents, smoke, and

loud noises scared nearby horses, and people were often injured or even

killed by panicking animals. With many new railroads coming into the

city in the

1850s, the horsecar companies built their lines to a different gauge

than the steam railroads. They generally used either 5'-2" or 5'-3" to

fall between the standard gauge of 4'-8 1/2" most railroads used and the

wide gauge 6'-0" tracks of the Ohio & Mississippi and CH&D

(which used dual gauge tracks). Later in the 19th century as the

various street railway companies consolidated, they standardized on a

5'-2 1/2" broad gauge that could be used by the existing 5'-2" and 5'-3"

equipment with little or no alterations. This is also called Pennsylvania trolley gauge since it was very popular there.

Even with the steel rails, the area's hills were still pretty much unscalable, since horses simply couldn't pull a loaded car up the slopes without great difficulty. Nevertheless, flat areas were opened up as much as possible. Horsecar lines extended along Eastern Avenue to Pendleton and north on Spring Grove Avenue through Cumminsville. There was a fairly extensive web of lines through downtown and the West End, as well is in Covington and Newport. Through the 1870s and 1880s the number of horsecar lines expanded into some of the hilltop communities like Mt. Auburn, Walnut Hills, and Price Hill, though service to those areas needed more than just horse power to make it viable for most commuters.

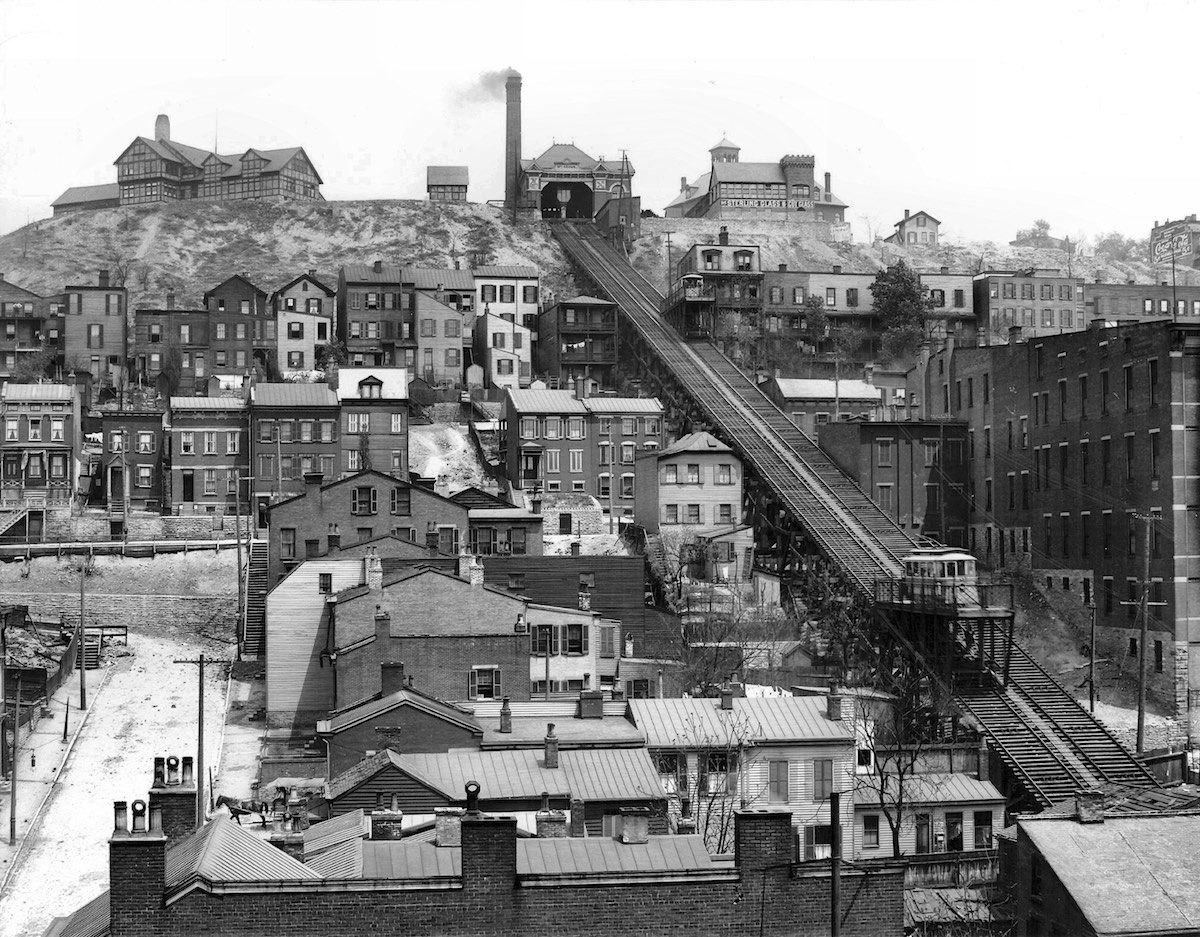

Inclined Plane Railways

The 1870s saw the construction of four of Cincinnati's five inclined plane railways. Using a steam engine (later converted to electric motors in some cases) and counterbalanced platforms on opposing inclined tracks, they allowed people, wagons, horses, and later electric streetcars and buses to climb the hillsides almost effortlessly. Upon reaching the top, where short-lived resort and overlook buildings were constructed, people could walk to their homes or catch another horsecar line to traverse the relatively flat terrain on top of the hills. Nonetheless, it could still be a time-consuming journey, requiring transfers from horsecar to incline to another horsecar.

|

The Mt. Adams Incline, Cincinnati's most famous and longest-lived. |

All the inclines operated in slightly different ways over the years, each with their own idiosyncrasies. The first incline built was the Mt. Auburn, or Main Street Incline, opened in 1872. It was unusual in that it did not have a consistent slope, being much steeper at the bottom than at the top. It originally had enclosed cars for hauling passengers, though they were later changed to open platforms to haul electric streetcars. A fatal accident occurred in 1889 when a car reached the top of the incline, failed to stop, and the cable was ripped out, causing the car to slide back down to the bottom of the hill out of control. All but one passenger were killed, and the stigma of this wreck never really wore off. The incline was the first to be abandoned in 1898.

The Price Hill Incline was the second to be built in 1874 with two enclosed passenger cars similar to the Mt. Auburn Incline. Two years later, a second set of tracks were built with open platforms to haul wagons. This is the only incline that was never purchased by the street railway, and thus it never hauled streetcars on either the passenger or freight side. The freight plane lasted until 1929, having hauled some private motor buses up and down the hill before closure. Passenger traffic that had been on a steady decline since the turn of the century actually rebounded through the 1930s, and it hit a high point in the last year of full operation in 1942, though it was only about a third of its maximum which was seen in the late 1890s. Perhaps it had become a bit of a novelty as other inclines closed down. Its poor condition a need for significant expensive repairs is what ultimately shut it down completely in 1943.

1876 saw the opening of the Bellevue Incline to foot traffic, and presumably wagons as well. The platforms were rebuilt to haul electric streetcars in 1890, with enough room left over for one or two wagons and pedestrians as well. The Bellevue Incline was abandoned in 1926, though carbarns at the top of the hill remained, and the streetcar line on Ohio Avenue was incorporated into a different route.

1876 was also the year the Mt. Adams incline opened with enclosed passenger cars. In 1879 they were converted to open platforms to haul horsecars. Eventually electric streetcars were brought up the hill on it, and for less than a year before it was abandoned in 1948 a motor bus route used it. This was the longest-lived of the five inclines.

The Fairview Incline was built much later than all the others, in 1892, by the Cincinnati Street Railway Company to serve their new crosstown line. At this time McMillan Street ended at Fairview and Ravine, so there was no other way for streetcars to get down the hill to connect with McMicken. The incline was deemed unsafe for streetcars in 1921 and enclosed car bodies were mounted on the platforms for pedestrians, an interesting reversal of the usual trend. This made the crosstown line excessively inconvenient, and instead of fixing the incline the street railway company built the extension of McMillan Street down the hill in 1923, at which point the incline was closed.

Cable Cars

Hilltop development was spurred by the inclines, but it didn't spread

too far past the crest of the hills. It wasn't until the introduction

of cable cars that reliable transportation between the hilltops and the

heart of downtown allowed neighborhoods like Walnut Hills, Mt. Auburn,

Corryville, and Clifton to develop significantly. Cincinnati had three

cable car routes, though what would have been the first in the city on

Spring Grove Avenue was blocked in court by the owners of

existing horsecar lines who feared competition. A route to Price Hill

was proposed, but it never came to fruition, probably due to difficulty

crossing the Mill Creek Valley and the expanding railroad yards.

While their 8-10 MPH running speed isn't impressive

by

today's standards, it tripled the distance people could live from the

center of town. Being pulled by a cable from a central plant meant that

hills were of no consequence. This is the main reason they still exist

in San Francisco to this day. Nonetheless, they were (and still are)

very expensive to

maintain in working order. The cables could last as little as six

months,

and it was difficult to keep debris out of the guideways. New cables

would take a full weekend to replace, and they would stretch

significantly after being put into service, by many tens of feet. In

some instances, this stretched cable would bunch up and snag a

car's grip, causing it to run out of control. Corners and

crossovers were often unpowered, with the cable running into a protected

guideway and series of pulleys. The car's gripman would have to let go

of the cable and coast to a place where he could get a new grip. A lack

of momentum could strand the car, requiring it to be pushed by hand.

Failure to let go of the cable could break the grip or damage the cable

and conduit. There were powered "pull turns" that used a series of

pulleys to guide the cable,

and cams would move the pulleys out of the way when a car went by.

These were quite expensive to construct, but they were needed in

Cincinnati because of all the turns at intersections and curved streets

climbing up the hills. Along

the entire length of a cable car line there were rollers at the bottom

of the conduit for the cable to move without dragging on the

bottom. When a car came along the cable would be lifted a few

inches off the rollers as it passed. These rollers, which were

spaced 30 to 40 feet apart, needed to be oiled daily, not to mention all

the other moving parts. Changing grade was also a challenge,

since transitioning from flat to uphill would normally cause the cable

to try to lift out of the conduit, so more special rollers and cams were

necessary to keep the cable in place but still allow the car and grip

to pass.

The cable car industry spawned numerous patents for

all these technologies, and its era of dominance was rife with lawsuits

and patent challenges. Most of the patents were for the grip

itself, which was actuated by a long lever in the cab. In the

conduit, the grip could be as simple looking as a large pair of pliers,

or as complicated as a Rube Goldberg machine with multiple pulleys,

guide wheels, levers, cams, hooks, springs, rods, and pistons on an

assembly the size of a refrigerator door. The relative simplicity

or complications were a result of the particular operating

characteristics of the line, such as the amount of curvature, grade

changes, pull curves, crossovers, operating speed, and so forth.

Overall Cincinnati's cable car lines were rather lightly built, possibly

because of the immense engineering challenges of the city's hills and

curved streets. This meant cheapening out on construction of the

conduit, which was the single most expensive part of the system.

Best practice was a conduit of iron and concrete, but some companies

used less concrete, thinner steel, or even wood in places. The Mt.

Auburn line used only iron conduit, which immediately led to expansion

and contraction problems, misalignment, and breakdowns. It's

generally regarded as one of the most cheaply-built cable car systems in

the country. The companies also saved money by not licensing the

various patented designs they used. Instead they'd build similar

but not quite the same equipment while mixing and matching technologies

as needed. This was common throughout the industry.

|

A typical single-truck cable car for the Mt. Auburn Cable Railway. Note the controls on each platform, allowing the cars to operate in either direction without turning around. |

The first cable car company to actually operate was the Walnut Hills Cable Railroad. In 1872, a horsecar line was chartered by the Walnut Hills & Cincinnati Street Railroad Company (called Route 10) to build up Gilbert Avenue. This line became a competitor to the Mt. Adams Incline, though it was not particularly successful, as it took the horsecars 30 minutes to climb the hill on Gilbert Avenue. Originally proposed by John Kilgour of the Cincinnati Street Railway Company, the cable car line was built by George Kerper, owner of the Mt. Adams Incline, after buying Route 10 from Kilgour. They planned to merge the two companies in the future. Limited service began on July 17, 1885. At that time, horsecars were brought to the bottom of the hill and the horses were unhitched, a detachable cable grip was attached to make the climb, then horses took over again at the top of the hill at the power house which remains today opposite Sinton Avenue and Windsor Street. This clumsy situation was remedied by October 1, 1886 after extension south to Broadway and north to Woodburn Avenue. Once completed in 1887, a loop was made from Broadway to 6th to Walnut to 5th and back to Broadway, with the outer end of the line terminating on a turntable at Woodburn and Hewitt, which was abandoned a year later in 1888 for a loop at Blair and Montgomery a few blocks further north. The carbarns were on Hewitt Avenue just east of Montgomery Road, but it is now gone. The line was converted to electric operation in 1898, though portions of the line had wires over it to provide a through route for electric cars to Norwood starting in 1889.

The second cable car line in Cincinnati was the Mt. Auburn Cable Railway, chartered in 1886 and presumably completed in 1887. The route between 4th and Sycamore and a terminal at Reading Road near Rockdale had simple crossover switches at each end, as double-ended cars were used and didn't need turning around. Trailers were used for most passengers however, and these needed to be shuffled around by hand at the ends of the line. They also operated a branch between 1888 and 1892 from Burnett Avenue along Erkenbrecher to serve the Cincinnati Zoo with a special steam dummy car. The power house and barns were at the corner of Highland and Dorchester. It caught fire in 1892 and was rebuilt. Consolidation in 1896 brought the line under the control of the Cincinnati Street Railway Company, and it operated until June 9, 1902. The Sycamore Street hill was too steep for electric cars to traverse however, so the rails were abandoned between Milton Street and Auburn Avenue in favor of an easier route up Liberty Hill and Milton to Highland Avenue. After abandonment, the power house sat empty for decades, and on February 22, 2021 the roof collapsed, reportedly due to heavy snow accumulation. Demolition of the building started on February 27.

The final cable car line built in Cincinnati was the Vine Street Cable Railway, opened in 1887 between Fountain Square and the company's carbarn and power house at Vine and Rochelle in Corryville. In 1888 the line was extended to a loop at Ludlow, Middleton, Bryant, and Telford in Clifton, though it was operated as a branch, so passengers had to change cars at Corryville. In early 1893 the cars from Clifton were run through to downtown, which required them to drop the cable and coast past the power house where the cable turned in to the building and came back out at a slightly different speed. The slower 8 MPH speed was between the power house and downtown, whereas the slightly faster 10 MPH speed was used between the power house and the end of the line. All three cable roads had this speed change and cars needed to do this maneuver when passing the power house. Sometimes there wasn't enough momentum to cross the gap, and the gripman or conductor had to push the car by hand. This company's power house and carbarn remained until the 1980s or 90s, used in the later years as studio space for UC's design school. The central utility plant now occupies the site, and Jefferson Avenue between Vine and Nixon was removed for the EPA building. This cable road was converted to electricity in 1898.

Steam Dummies

Before moving on to electric streetcars, mention has to be made of a

short-lived and somewhat obscure method of transportation, the steam

dummy. It was basically a small railroad locomotive built to look like a

trolley car, so it wouldn't scare horses like a normal railroad

locomotive might. They generally weren't successful in that regard, and

were prone to frequent breakdowns and complaints due to smoke and noise.

Mention has already been made of the steam dummy branch line operated

by the Mt. Auburn Cable Railway. It opened in 1888 and ran from Burnett

Avenue west along Erkenbrecher to serve the Cincinnati Zoo. This was a

sort of hybrid steam dummy cable car. There was still a cable slot

between the rails, but the cable was fixed at each end, and the steam

engine operated a pulley in the car which engaged the cable to drive it.

This peculiar system lasted only four years until 1892 when the city

repaved the road and tore up the rails, not allowing the railway company

to restore them.

|

The Mt. Lookout dummy car at the Brannan station, approximately the location of Mt. Lookout Square today. |

The other steam dummy line in the city was located in the East End and Mt. Lookout. It is much better known than the very short-lived dummy on Erkenbrecher, and it was a bit more conventional since it didn't need to use pulleys to engage a cable. The project was the brainchild of John Kilgour's brother Charles, secretary of the Little Miami Railroad. He built the Pendleton & Fifth Street Market Space Street Railroad running from Fountain Square into Fulton via Eastern Avenue in 1860. It was extended to the west edge of Pendleton in 1863, at what is today St. Andrews Street. Being a few miles long already, it wasn't possible to extend the line much farther using horse power. Extension was needed though, as there was already an established community in Columbia, and new estate development in Mt. Lookout where the Kilgours had built a house. The Little Miami Railroad provided infrequent and expensive service unsuitable for commuting, so the decision was made to extend the horsecar line with a steam dummy.

The Cincinnati & Columbia Street Railroad was chartered on December 5, 1863 to build a single track route from the end of the existing horsecar line at St. Andrews Street on Eastern Avenue to Carrell Street, with a passing siding near Delta Avenue. They used a 5'-2 1/2" gauge, and opened for regular service on June 24, 1866. While traffic was light, and they still had trouble with frightened horses, the Kilgours wanted to develop their extensive real estate holdings in Mt. Lookout. On March 14, 1871, they received permission to build a branch up Crawfish Road, today's Delta Avenue, to Erie Avenue. This branch was built with 3'-0" narrow gauge tracks (and the existing line on Eastern Avenue was converted to match) on an alignment significantly different from today's Delta Avenue. The original Crawfish Road was much more twisty and narrow, with many undulations that were smoothed out and bypassed later on. It was much like Clough Pike is today, and a lot of the valley has been subsequently filled to bring the grade up to a more manageable level, and to give a little more room to build on either side. Little of the old street remains, except for the lower part of Empress Avenue, which appears to be the original road. The dummy branch had to be built off to the side of the old road on its own right of way, but because the now gone Crawfish Creek's valley was so much deeper than today, the dummy line still had to contend with some very steep grades. The branch was completed to Mt. Lookout Square in July 1872 and operations began, while final completion to Erie Avenue didn't happen until 11 months later.

As the neighborhoods developed, little news of the steam dummy was reported. However, by 1886 there were rumblings from the community to replace the unsatisfactory service with cable cars. Little investment was made in the dummy line since it was primarily a venue to increase real estate prices and attractiveness for the Kilgour's land, much like other suburban railroads. Nonetheless, the East End line was purchased by the Cincinnati Street Railway, upgraded to electric operation, and converted back to broad gauge tracks by 1891. The Mt. Lookout branch was left to flounder with the steam dummy cars a while longer. In 1896 it was finally brought into the Cincinnati Street Railway Company, and it was viewed as a good link between the East End car line and the Erie Avenue car line which had opened in 1894 and terminated at a loop next to Delta Avenue at what was then St. John's Park. Abandonment was delayed until 1897 when re-grading of Delta Avenue was completed and tracks could be laid in the new road.

One last very obscure steam dummy was operated by the Newport and Dayton Street Railway in Kentucky. The company experimented with two cars that were run from October 22, 1877 to February 2, 1878. At that date Newport filed a court order banning the contraptions which they deemed a nuisance. The company tried hitching horses to them but this was deemed impractical and the line reverted to horsecars.

Electric Streetcars

In 1888, just after the cable car lines were completed, the first

electric streetcar service began in Cincinnati. It was done by George

Kerper's Mt. Adams & Eden Park Inclined Railway Company, owner of

the Mt. Adams Incline and the Walnut Hills Cable Railroad. This company

electrified their horsecar line on McMillan Street from Gilbert Avenue

to Oak Street and Reading Road. Later that year, Kerper received

permission to build a line to the B&O Railroad in the middle of

Norwood. There never were horsecars in Norwood, so this was the first

brand new all-electric line, extended along Montgomery Road from the end

of the Walnut Hills Cable Railroad's terminal loop at Blair Avenue in

Evanston. This route came from downtown up the Mt. Adams Incline,

through Eden Park to Nassau, then followed Gilbert to Montgomery,

running over the cable car tracks from Nassau to McMillan, and between

Gilbert/Hewitt and Blair in Evanston. The first electric route in

Covington was the Madison Avenue line, which operated as a shuttle

starting in 1890 until negotiations were settled with the Suspension

Bridge owners and Cincinnati to install wires to Fountain Square early

in 1891.

|

An early electric streetcar, towing one of the trailer cars of the Walnut Hills Cable Railroad. |

These earliest cars had a single large trolley pole but collected power from two closely spaced wires. It didn't take long for the wires to be spread farther apart to prevent short circuiting, and two separate trolley poles were used. This early setup was likely due to the horsecar era rails not being electrically bonded, so they couldn't be used for the return current. Attempts to do so by the Cincinnati Inclined Plane Railway Company, owner of the Mt. Auburn Incline, caused the telephone company to file a lawsuit in 1890 to prevent the street railway companies from using rail returns, saying current leakage caused static on their underground phone lines. There were also restrictions on digging up streets, so properly bonding existing horsecar or cable car tracks wasn't always possible. The effects of current leakage are well documented, and they can accelerate corrosion of underground conduits and piping due to electrolytic reactions. Even new systems can have this problem, and there were issues in Salt Lake City with increased corrosion of water mains near a new light rail line.

An injunction required that only dual overhead wires could be used within the city limits until a ruling in the trial. The case dragged on, and even though the street railway eventually won, by then so much dual overhead had been installed that it became the standard for the system. With the presence of the dual wiring, the rails were not bonded electrically, so interurbans operating over the street railway had to be equipped with double trolley poles, though they only used them when on street railway trackage. Some interurbans like the IR&T used dual overhead within the city limits even on their own tracks, while others used single overhead, only switching when they came onto the street railway tracks, such as the CG&P. Even street railway cars would use single overhead outside the city limits, such as on route 78 to Lockland, which would take down the second pole upon entering St. Bernard. Though Carthage and Hartwell, through which route 78 ran, were annexed in 1911 and 1912 respectively, they kept single overhead since it was already setup that way beforehand. The Northern Kentucky lines were also affected by this, with dual overhead on the bridges over the Ohio River, and most streetcars putting up or taking down the second pole on the Kentucky side of the river.

While Cincinnati was the only major city in the United States to operate dual overhead wiring for streetcars, the rest of the electrical infrastructure was pretty typical. The first power plants were located along with carbarns in Brighton on Harrison Avenue, Mt. Auburn on Reading Road, and Pendleton (East End) on Eastern Avenue. The streetcars themselves were powered with 600 volt DC current, though since DC current can only travel a few miles, substations connected by high voltage AC transmission lines were built throughout the city and surrounding areas to make sure enough power was available. Early substation were located at each of the three power stations, as well as in Lower Price Hill, Price Hill, Over-the-Rhine, Cumminsville, Evanston, Hartwell, and East Hyde Park. The Kentucky lines ran on 550 volts DC, though they could operate just fine over the tracks of the Cincinnati Street Railway. The company's main power plant was in Newport along with their barns and shops near 11th Street and the Licking River.

The Mt. Adams & Eden Park Inclined Railway Company expanded their electric operations throughout the remainder of the 1880s and early 1890s. Kerper resigned in 1890, but work continued under new management and a new line on Madison Road to Hyde Park was built. In 1893, a joint venture with the Cincinnati Street Railway Company saw construction on McMillan Street between Gilbert and Ohio Avenues. The company finally became a part of the Cincinnati Street Railway Company in 1896. Even before acquiring the Mt. Adams company, the Cincinnati Street Railway was already the largest operator in the city. After seeing the success of Kerper's first electric line, they electrified their Colerain Avenue route to Cumminsville in 1889, and they bought the East End line through Pendleton on Eastern Avenue to Columbia at Carrell Street in the same year with plans to electrify it. Conversion was completed in 1891 as mentioned earlier.

This was also a busy time for expansion of the Northern Kentucky system as well. After the typical mergers and acquisitions, the dominant company was the Cincinnati, Newport and Covington Railway, also known as the Green Line due to its paint scheme. The early 1890s saw extensions being opened to southern parts of Covington, specifically to Rosedale and Latonia. The long line to Ft. Thomas also opened in 1893 as was the line to Ludlow and Bromley. The route to Evergreen Cemetery in Southgate was also opened in 1894. Opening of the Central Bridge in 1890 allowed some of the Newport routes to be directed over that bridge to reduce congestion and running time over the nearby L&N Bridge.

1896 is a year that has been mentioned a number of times already, as it was the date of final consolidation of all the disparate companies into the Cincinnati Street Railway. The only parts not consolidated were the lines in northern Kentucky, and the Vine Street line north of the zoo, which went to John Kilgour personally, as it was to be part of his Millcreek Valley Line (the Cincinnati & Hamilton interurban). In 1901 the Cincinnati Street Railway leased all of its property to the Cincinnati Traction Company to operate and maintain all the lines. This was done to retire outstanding mortgage bonds and increase the capital stock available to the system. 1902 saw the first double-truck cars on the system, though some single-truck cars were still ordered a few years later due to their reduced power requirements, as the electrical system was over capacity. The rails themselves were nearly at capacity as well, and traffic jams were a serious problem around Fountain Square, which every line that came downtown passed. More and more cars were ordered, and electrical capacity was increased while some routes were shifted a block or so away from Fountain Square to reduce congestion.

In the waning years of the 19th Century and the first ten years of the 20th, the street railway system was mostly built out. The three branches in Norwood were built at this time, as well as extension along Montgomery to Fenwick. Lines were extended up Elberon and out Glenway and Warsaw, shutting down the last horsecar line in the city, the Price Hill Jerky, which operated from the top of the Price Hill Incline to Hawthorne and Warsaw until 1904. More lines were extended to Madisonville and Oakley, as well as to Cheviot, College Hill, and Lockland. This is also the time many interurbans started operation, and some of their tracks eventually became extensions of existing streetcar lines that they fed into.

The last major new route in Kentucky, the line to Ft. Mitchell, was also opened in 1902. The first section only went as far as Lewisburg, with an extension in 1903 to Highland and St. Mary's Cemeteries, and final completion to Orphanage Road happening in 1910. A new loop of tracks through south Bellevue also opened in 1904. In 1907 the Columbia Gas and Electric company also purchased the Cincinnati, Newport and Covington Light and Traction Company, then owner of the Green Line, to get control of the electric and gas franchises and facilities. They couldn't buy only the gas and electric portion, so they somewhat begrudgingly took on the Green Line as well. This actually proved to be a huge boon for the Green Line, since it had the financial backing of a fast growing utility company to underwrite any potential losses for the traction business. While this relationship was ultimately doomed by the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, the breakup didn't happen until just after World War II.

1910 also saw the incorporation of the Newport and Alexandria Interurban Electric Railway Company, whose purpose was to build an interurban to Alexandria from the end of the Ft. Thomas Line and to operate over it to reach Cincinnati. Various difficulties stalled right-of-way acquisition until 1916, and growing doubts about the future of the industry, on top of entering World War I, had dried up the capital of the company. By 1918 only 1.3 miles of track had been built, and the Green Line acquired it for salvage value and operated it as a shuttle. The short extension lasted only until 1924 before it was abandoned.

The 1910s and 20s saw little additional construction of new lines compared to previous decades. Existing lines were extended, such as adding track along Glenway to Ferguson, or taking over part of the IR&T on Montgomery from Fenwick to the city limits at Coleridge, and various minor connections were made such as the completion of McMillan Street down the hill to connect with McMicken. 1916 saw the opening of the last completely new streetcar line in Cincinnati, Route 42 to Bond Hill via Paddock Road. Unable to reach the heart of Bond Hill due to a new law prohibiting streetcars from crossing railroads at grade, it never saw great patronage, especially for passing through essentially unsettled areas around the Avon Field golf course. A motor bus line was started in 1926 along Paddock Road to Lockland, providing easier access than the streetcar. Grade separation of the B&O Railroad crossing on Paddock in 1927 only served to destroy the turnaround loop for the line, and it wasn't repaired. Instead they used a double-ended jerky car until 1928 when reconstruction of Reading Road severed the connection to the rest of the system, and this last streetcar line to be opened was also the first in Cincinnati to be replaced with motor buses.

|

A typical Cincinnati Street Railway car turning onto Wilder Avenue from Warsaw Avenue. This shows the "traction orange" paint scheme that was common in many transit systems around the country. |

The 1910s also saw some abandonments in Kentucky. In 1917 the city of Newport decided to repave Patterson Street with asphalt to make it better for car and truck traffic, and they tore up the streetcar tracks in the process. They told the street railway company to put back their tracks and repave the rest of the road, but they refused, arguing that the tracks and the road were fine before. Newport did not prevail in the ensuing legal battle since they violated the franchise agreement, and Patterson Street lost transit service until buses were introduced in 1936. There was also complaining among the merchants on Monmouth Street that streetcars were blocking automobile traffic, so they successfully campaigned to have the tracks removed between 5th and 11th Streets and to divert the remaining service to existing tracks on York, just one block away. The store owners would come to regret that decision as they lost much more foot traffic than they gained from automobiles.

The most significant project during this time period was the construction of Dixie Terminal, which opened in 1921. This office building and streetcar terminal, which still exists at the corner of 4th and Walnut, greatly reduced travel times for Kentucky streetcars by consolidating all their terminal operations into one building. Covington cars entered the upper level of the terminal from the Suspension Bridge by dedicated viaducts over 3rd Street. Newport cars used the lower level which they accessed from 3rd Street after crossing the Central Bridge to Broadway Street. This new facility removed all the Kentucky cars from the already horribly congested 4th and 5th Streets and Fountain Square, saving 5-10 minutes of running time. At this same time the Green Line also stopped using the L&N Bridge and routed all their Newport division cars over the Central Bridge. This shortened the distance to Dixie Terminal, saving the rental fees, maintenance, and traffic bottlenecks on the L&N Bridge.

The mid 1920s saw a significant investment being poured into the street railway in Cincinnati, despite the lack of any significant extensions. Many streets and their tracks were completely rebuilt, including Hamilton, Erie, Madison, and Delta Avenues, among many others. There was also a big move to improve the electrical system as well. The East End/Pendleton power station and barns were closed, and extra power as needed was bought wholesale from the electric company. This move also saw the building of many new fully automatic substations and upgrading of a few older ones, since traffic was increasing and the newer cars were bigger, heavier, and drew much more power than early electrics. New substations were built in the West End near Union Terminal, in Westwood, Camp Washington, Winton Place, Elmwood Place, O'Bryonville, and Columbia-Tusculum. The Green Line in Kentucky also phased out their own power generating facilities around this time as they were becoming outmoded. The Newport power house was gradually relegated to a substation as the new West End power station in Cincinnati was brought online between 1918 and 1923. Other substations for the northern Kentucky routes were at Stewart and Madison in Covington, 35th and Decoursey in Latonia, and on Dixie Highway near today's I-75 interchange.

The Cincinnati Subway

The 1920s, was also the time of the ill-fated Cincinnati subway. The

Cincinnati Street Railway was contracted to operate it so it deserves

mention as part of the overall history of the city's streetcars and

transit. The broader history has been spun off to its own page here.

PCC Cars, Trolleybuses, and the End of the Line

The 1930s was a time of transition for many street railway companies, with the Great Depression causing reduced ridership and putting pressure on the companies to economize and modernize their operations. While Cincinnati ridership peaked near 100 million in 1929, with about 30 million in northern Kentucky, it dropped by some 40% at the worst part of the Depression. The streetcar was still king of operations, but the writing was on the wall. The early part of the decade saw the opening of the Western Hills Viaduct in 1932 to replace the obsolete Harrison Avenue Viaduct just a short distance south. While this new viaduct improved streetcar service to Fairmount and Westwood, it also greatly improved automobile access to those same neighborhoods. The same was true later in the decade when Columbia Parkway was opened in 1938. The East End car line got some new private right-of-way along the highway, but the significantly reduced travel time for motorists to East Walnut Hills, Hyde Park, Columbia-Tusculum, Mt. Lookout, Linwood, Fairfax, and Mariemont ultimately led to the collapse of all the east side streetcar lines. For that reason, Columbia Parkway basically killed off Peeble's Corner, which depended on the high number of passengers going through there and transferring between lines.

.jpg) |

A special railfan trip featuring a newer yellow PCC streetcar on Montana Avenue at the end of the 21 Westwood Cheviot line, with an older car to its left, and the trolleybus that would eventually supplant them both sneaking around them in the back. Taken on April 22, 1951 just one week before final abandonment of the streetcar system, this was the group's farewell fan trip. The trolleybus was being used for operator training in preparation for the 21 line being converted to trolleybus the following Sunday. Information provided by Bill Myers, an attendee on this trip. |

1936 saw the introduction of the first electric trolleybuses to Cincinnati, on the Clark Street line that traversed Spring Grove Avenue to Chester Park. The tracks on Spring Grove Avenue needed replacing, and the street had to be repaved. To avoid the cost of renewing the tracks, the traction company decided to try out trolleybuses on this line. These vehicles were an easy sell in Cincinnati since the dual overhead wiring needed for them was already in place. Changes had to be made at switches and crossovers, but in general little other modification was necessary. They proved their versatility by being able to maneuver around other vehicles while still remaining connected to the wires. Being electric, they were much quieter than gasoline or diesel buses, and they were probably quieter than the streetcars they replaced, since they had rubber wheels instead of steel. The trial was successful, and a few other lines were converted, but the coming of World War II would temporarily halt the changeover of much of the system.

At the same time, the Green Line in Kentucky was being decimated by private bus competition. Kentucky didn't begin restricting competing bus lines until much later than Ohio, so the effects were much more acute. The Green Line responded in part by introducing some of its own bus lines and extending other routes with buses. They also converted the 6-Rosedale and 7-Latonia routes to electric trolleybuses in 1937 after adding a second overhead wire. The main reason for this was to abandon the worn streetcar tracks on these heavy-haul lines, but also to retain entrance to Dixie Terminal, which only allowed electrically powered vehicles to enter the building. The 3-Ludlow route was also converted to trolleybuses in 1939, and this would be the last electric conversion on the Kentucky side of the river. With the Green Line trying to outcompete other bus lines, buying out competitors and acquiring their vehicles, and with concerns about flood-prone routes that were just as troublesome for trolleybuses as for streetcars, northern Kentucky saw an earlier and more gradual switchover to gasoline and diesel buses than Cincinnati.

At the time the trolleybuses were being tested out, a new type of modern streetcar was also brought in for evaluation. The sleek PCC cars, developed by a committee of street railway company presidents, were intended to modernize streetcar fleets across the country and breathe new life into the systems by using a common interchangeable design. These new cars were lightweight, quick-accelerating, smooth, comfortable, and they saved on electricity and track wear. Three cars were ordered in 1938 for evaluation, all built to the new PCC specifications, but each from a different car company. One was built by Pullman-Standard, another by Brilliner, and a third by the St. Louis Car Company. Ultimately, the decision was made to go with the St. Louis cars, and several were ordered in late 1939. The second and last order of new PCC cars came in July 1945, only 6 years before the system was abandoned, when the remaining PCC cars were sold to Toronto. PCC cars were not operated on the Kentucky lines, which used many old streetcars, even single truck ones, until the very end.

Despite how well received the PCC streetcars were, the priority in the 1940s was to make more room for automobiles. The streetcars ran down the middle of the streets, and their station platforms were considered obstacles to automobile traffic flow. While World War II put a halt to some plans to convert lines to trolleybus or motor bus because of rubber tire and gasoline rationing, once the war was over conversion happened swiftly. After the war, most of the street railway system was still in use, and there was even some track rehabilitation done in 1946. Nonetheless, starting in 1947 there was a big push to convert routes to trolleybuses, and the last few streetcar lines were abandoned on April 29, 1951. Of those last routes, all were converted to trolleybus except one, Route 78 to Lockland. The longest and one of the busiest lines in the system, it was replaced with diesel buses. So while that was the last streetcar line closed, it also marked the end of any new trolleybus lines as well.

Since no rail lines were operating anymore, the street railway company changed its name to the Cincinnati Transit Company. The quiet and smooth operation of the trolleybuses couldn't recapture the many people leaving the city and foregoing public transportation however. Ridership, which was near its 100 million per year peak even in the late 1940s, was dropping significantly through the 50s. Even without the burden of track maintenance, the electrical system was seen as a further area to economize, and diesel buses began to replace trolleybus lines. This was a bit more gradual than the retiring of the streetcars, but the end of electrically powered transit in Cincinnati came on June 18, 1965 when Route 61, Cilfton-Ludlow was converted to diesel. Several of the coaches in good condition were sold to Dayton, which still operates a fleet of trolleybuses today.

|

A trolleybus turning around at the end of the Fairview loop, the former location of the Fairview incline. |

With conversion to motor buses already in full swing in Kentucky before World War II, it didn't take long for them to finish the process after record wartime ridership numbers had thoroughly beat up the system. The Ft. Thomas route was converted to buses in 1947, operating along Waterworks Road until the early 1950s when the old private right-of-way was sold off and paved as Memorial Parkway. At the very beginning of 1948, after conversion of 4-Main and 5-Holman in Covington to motor buses, only the long Ft. Mitchell streetcar line remained. July 2, 1950 was the last scheduled run of that line, though on July 3 the car "Kentucky" was brought out to Park Hills to be towed to the Behringer-Crawford Museum in Devou Park for display, at which point the electricity was turned off. Ridership crashed throughout the 1950s, and the upcoming construction of Ft. Washington Way and I-75 was going to require the construction of temporary overhead to maintain service on the remaining trolleybus lines. To avoid that expense, on March 17, 1958 northern Kentucky was entirely motorized when the three trolleybus lines were dismantled.

The Cincinnati and northern Kentucky systems struggled through the 1960s and were completely bankrupt by the 1970s. The now ubiquitous bus lines were still plagued with high costs from ever increasing employee salaries and further erosion of ridership due to government funded road and highway expansions. The expanded highways did allow for some longer-haul operations to operate fairly quickly, but transit service to suburban locations was and remains rather inefficient. The only real bright spot in the situation was the Green Line's service to and from the new Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport. They had already been running buses to there to carry construction workers, but overall ridership for transporting employees and some travelers routinely exceeded expectations. After I-75 was built, it cut about 10 minutes off travel times, and it had become the one bright spot in the Green Line's failing business. Still, like many transit systems across the country, there was a negative feedback loop where ridership dropped, then fares would have to be raised and service cut, thus leading to further reduced ridership and starting the cycle all over again.

In 1972 the Green Line was out of business, and with the new availability of Federal funds, voters in Northern Kentucky agreed to take over the defunct system, creating the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK) to keep the buses running. In 1973, the Cincinnati Transit Company was also out of business and absorbed into the new Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA), and the bus system was named Queen City Metro. SORTA also began operating a small fleet of Access buses for disabled riders who can't use the regular bus system. Metro abandoned the historical orange and cream color scheme for white and black buses with a blue and purple stripe. This has been more recently supplanted by a green and blue scheme on a white background that tries to play up the green aspects of transit. TANK buses use a blue and green livery that pays at least a small homage to the historical Green Line. While still separate organizations, SORTA and TANK entered into a comprehensive cooperation agreement in 1999 that attempts to better coordinate the two systems. While ridership numbers are just a small fraction of what they were in the 1920s or during World War II, both Metro and TANK buses continue to serve Cincinnati and northern Kentucky on some of the same routes as the original omnibus and horsecar lines of 150 years ago.

Epilogue

For nearly 100 years, Cincinnati's growth outside the downtown basin

was enabled by its street railway system. From slow horsecars to cable

cars to inclines and electric streetcars and trolleybuses, there was an

extensive network of relatively quiet, frequent, and well-patronized

public transit. The cable cars and electrically powered streetcars and

trolleybuses did not pollute the air where they ran, and they provided

the framework for the city to grow outward. Every neighborhood within

the city limits, except for Mt. Airy and Roselawn, had either streetcar

or interurban service, and all of it is gone today. It's a risky

proposition to dismantle a system which essentially built a whole city.

Imagine what would happen if pedestrians were banned from downtown, or

if automobiles were no longer allowed to operate in Indian Hill or

Fairfield. It's no surprise then that many of our neighborhoods are

dysfunctional today.

Road projects like Columbia Parkway diverted people away from important transit routes and opened up new areas to sprawling development. However, the construction of I-75, I-71, I-74, and the Norwood Lateral aggressively tore through already built-up neighborhoods. These roads demolished hundreds of buildings, displacing thousands of people, and they encouraged the development of new neighborhoods way out on the fringe, much farther out than anyone using a streetcar could imagine. Because of this, the city itself has lost significant population and tax revenue, and without any meaningful public transportation left, the whole region is choked with traffic while it doesn't have to be.

A new electric streetcar loop opened on September 9, 2016, running from 2nd Street at The Banks to Henry Street near the base of Bellevue Hill in Over-the-Rhine. It operates as a circulator similar to the early horsecar lines, allowing people to get around more quickly and supporting walkable urban neighborhood development. Despite some teething problems and city politicians who wanted to abandon it mid-construction, and who continue to do everything in their power to hobble the system, one hopes that it is but the first in a long line of better transit so that Cincinnati, and the whole region, can move forward to a better future.