Dayton & Cincinnati Railroad

(Dayton & Cincinnati Short Line/Dayton Short Line)

Former Dayton, Lebanon

& Deerfield/Springboro, Lebanon & Cincinnati/Dayton &

Cincinnati/Cincinnati Railroad Tunnel Company

Dual standard/wide gauge (6'-0") railroad proposed

between Cincinnati and Dayton in the mid 1850s via deep level Deer Creek

Tunnel under Walnut Hills

Downtown terminal: Court and Broadway Streets

Never completed

There was no shortage of ambitious railroad plans

for Cincinnati in the decade of the 1850s. This period saw construction

of many of the Kentucky railroads, opening of the various B&O

lines into the city, and most notably, the start of the Dayton Short

Line's ill-fated deep level Deer Creek Tunnel under Walnut Hills. First

incorporated in February 1847 as the Dayton, Lebanon & Deerfield

Railroad, the fledgling company was renamed the Dayton, Springboro,

Lebanon & Cincinnati Railroad in February 1848, and the Dayton &

Cincinnati Railroad in February 1849 (routinely referred to as the

Dayton Short Line). Their goal was to build a double-track dual-gauge

(standard and 6'-0" wide gauge) railroad from the northeast corner of

downtown Cincinnati to Dayton. It would roughly parallel the routes of

the later CL&N and PRR Richmond Division

to Sharonville where it would head due north to Middletown and follow

the east side of the Great Miami River Valley to Dayton. This route that

bypassed the Mill Creek Valley and Hamilton was more than seven miles

shorter than the competing CH&D. Ultimately, the former Big Four/NYC

route to Columbus used pretty much this same route between Sharonville

and Middletown. Also at Sharonville, the Dayton Short Line would

connect with an extension of the Hamilton & Eaton coming in from the northwest, and the Cincinnati, Lebanon & Xenia, a potential competitor to the Little Miami Railroad, coming in from the northeast. At Norwood it would connect with the Marietta & Cincinnati, and the Cincinnati & Eastern would join the route near Idlewild.

|

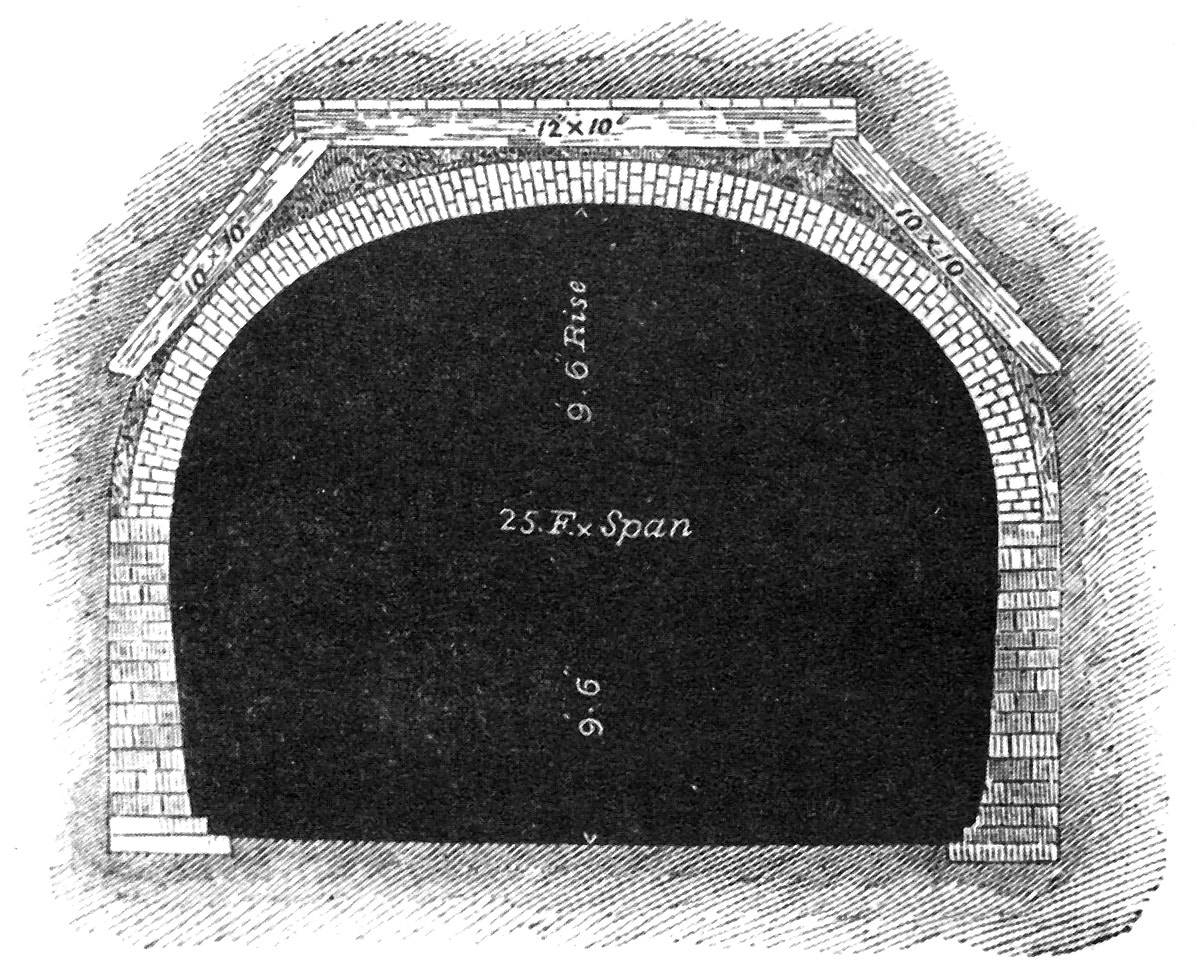

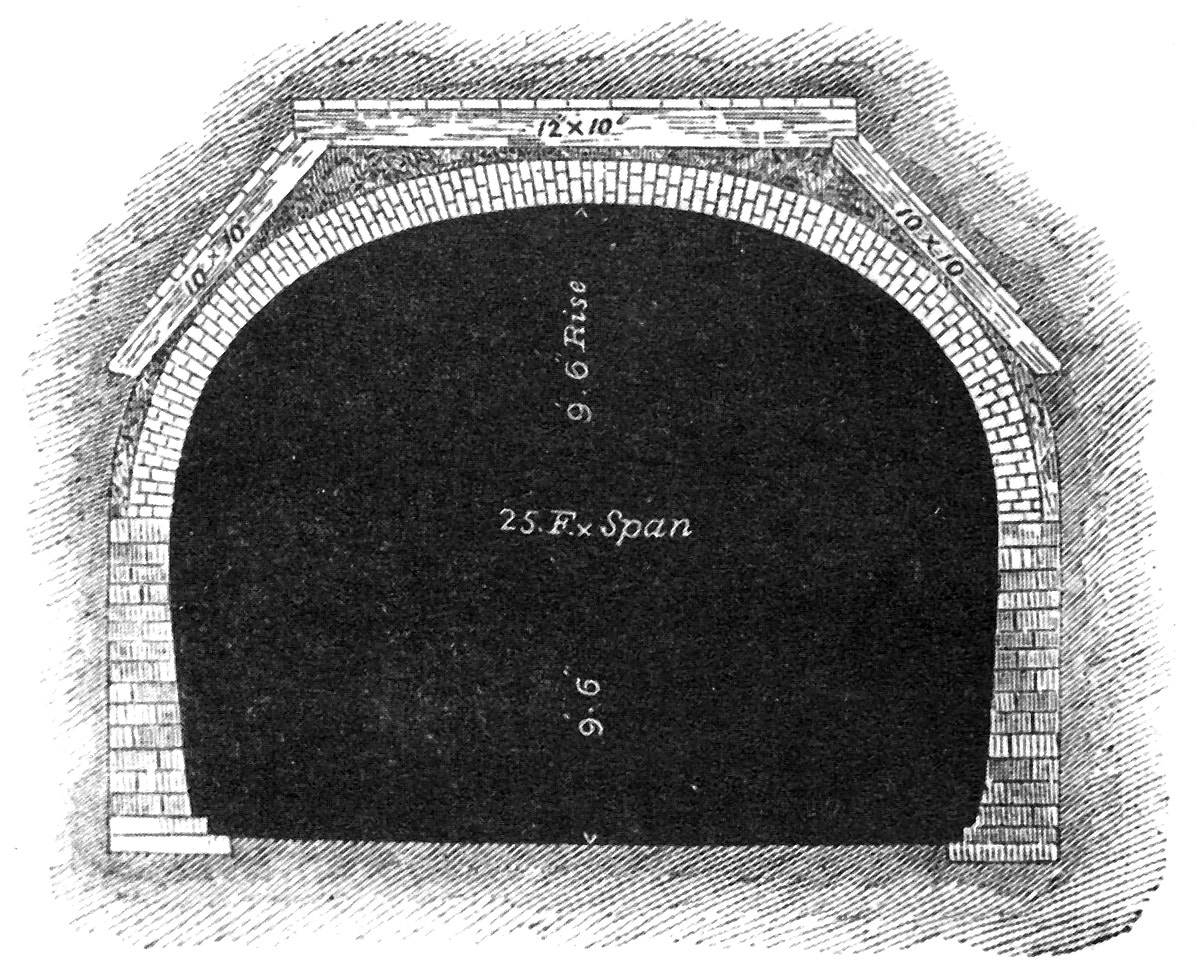

Cross-section of the

Deer Creek Tunnel under Walnut Hills. The width at the widest point is

25 feet and the total height is 19 feet. The flattened elliptical

profile of the arch allows for better clearance to the outside top edge

of rail cars. From "Narrow Gauge in Ohio" by John W. Hauck. |

A major advantage of the Dayton & Cincinnati

route, aside from its shorter distance and easy grade to points north,

was that it is entirely immune to flooding. Until large flood control

projects were brought online after 1937, the Mill Creek Valley was

regularly plagued by rising waters. Flooding from the creek itself was

certainly an issue, but water backing up the valley from the Ohio River

was a much bigger concern, since this would regularly strangle railroad

operations, blocking all routes to the north. The Little Miami Railroad was subject to rising water from the Ohio and Little Miami Rivers as well, while the L&N and C&O

tracks in northern Kentucky were prone to floods by the Ohio and

Licking Rivers. So not only would the approach tracks of the Dayton

& Cincinnati be safe from flooding, the terminal area at Court

Street is also on high ground as well. This was a big selling point.

With many railroads planned or already under

construction, they needed a final route to their proposed downtown

Cincinnati terminal at Reading Road (at the time known as either Hunt

Street or Lebanon Turnpike) and Pendleton Street. This first alignment

designed by engineer Erasmus Gest would run the tracks along the west

side of Reading Road for about a half mile north, then it would cross

Reading and the Deer Creek ravine to a 5,500 foot tunnel starting above

Florence Avenue, presumably near Boone Street. Due to the grades

involved in reaching the tunnel, and the terminal area becoming built-up

and unsuitable for rail use, the terminal was moved to Broadway

between Reading Road and Court Street. This site being about 35 feet

lower than Pendleton Street required the tunnel length to nearly double

to accommodate the grades and hill profile.

This lengthened Deer Creek Tunnel would be the

Dayton Short Line's centerpiece. The ambitious project called for a

10,011 foot long tunnel, with 7,903 feet of it being bored directly

through the hill. The remaining 2,108 feet of approaches (1,525 feet on

the south end and 583 feet on the north) was to be cut and cover

construction. Had it been completed before 1875, when the Hoosac Tunnel

in Massachusetts opened, it would have been the longest tunnel in the

United States. The 25 foot wide by 19 foot tall tunnel would be walled

with stone and arched with brick. This generous size for the time was

enough to accommodate the two dual-gauge tracks at an easy grade of 39.6

feet per mile, or 0.75%.

The aforementioned Hoosac Tunnel was in many ways

the big brother of the Deer Creek project, and its history illustrates

how the fortunes of Cincinnati's tunnel could have played out under

different circumstances. In the early 1840s the Western Railroad

was built to connect Boston and Albany through the southern part of

Massachusetts via Worcester, Springfield, and Pittsfield. However,

railroads in the northern part of the state were cut off from the Hudson

Valley by the Hoosac Range, an extension of Vermont's Green Mountains.

In 1848, Alvah Crocker, a paper mill owner from Fitchburg, chartered the

Troy & Greenfield Railroad to connect its respective cities with a railroad tunnel through Hoosac Mountain.

This tunnel would be 25,081 feet long, almost

exactly 2.5 times the length of the Deer Creek Tunnel. With an estimated

construction cost of $2 million, ground was broken on January 8, 1851.

Technical, financial, and political problems would plague the project

over its 25-year construction. Early tunnel boring machines broke down

and were discarded after only a few feet of test digs were completed.

The east end had to contend with hard quartz and gneiss that resisted

blasting, and the west end was filled with unconsolidated ground up

limestone soaked with water that resembled quicksand. By 1860 after a $2

million loan from the state and a change in contractor, barely 500

feet had been excavated from the west portal, even after two shafts had

been dug from above to create more working points, and 1,810 feet had

been excavated from the east portal.

The Western Railroad, led by Chester W. Chapin,

opposed the Hoosac Tunnel and its northern route through the state, in

much the same way as the CH&D and Little Miami Railroad were

threatened by the Deer Creek Tunnel and the Dayton & Cincinnati's

shorter approach to Cincinnati. Chapin successfully lobbied to block

state funding of the tunnel in 1861, which bankrupted and temporarily

stopped the project. In 1863 the state, with Alvah Crocker now

superintendent of railroads, restarted the project, and in 1868 the

Massachusetts legislature appropriated $5 million to complete the

tunnel. Had the political winds not changed through Crocker's deliberate

intervention, the Hoosac Tunnel could very well have died just like the

Deer Creek Tunnel. In this case however, construction marched on while

several chief engineers came and went over the next decade. A large

central shaft for digging and future ventilation was added to the

project, and advances in technology like nitroglycerin and compressed

air drilling moved things along. The first train ran through the tunnel

on February 9, 1875 and the state of Massachusetts declared the tunnel

officially open on July 1, 1876 after finishing of archwork and cleaning

up tight spots. The total cost was around $20 million and 195 lives

lost.

The design of the Hoosac Tunnel is similar to Deer

Creek in many ways. It was also planned to have two tracks, although it

wasn't until 1885 that the second track was finally installed. The

primary design difference is that the Hoosac Tunnel has a circular arch

versus Deer Creek's elliptical arch. They both have slightly buttressed

side walls, but Hoosac is 24' wide by 20' tall and Deer Creek is 25'

wide by 19' tall. Because of the different arch profile, the effective

clearances were probably pretty similar. Both tunnels are perfectly

straight, which made surveying much easier, and it allowed for a

narrower profile since curves need a wider cross-section to accommodate

the same size train. While The Deer Creek Tunnel slopes up from south to

north at a grade of 0.75% the Hoosac Tunnel's portals are both at the

same elevation, although there is a 0.5% slope up to the middle to allow

for natural drainage out each end. The other difference is that no

vertical shafts were part of the Hoosac Tunnel's original design,

whereas Deer Creek had three shafts about 200 feet deep which were

located throughout Walnut Hills. The Central Shaft at Hoosac was a later

design addition to aid in digging. Although it was widened and large

fans were added for ventilation after the tunnel was completed, smoke

was still a major problem that prompted the use of electric locomotives

in 1911 until cleaner-burning diesels were available and the electric

catenary was removed in 1946. Ultimately due to declining traffic, the

Hoosac Tunnel was reduced to a single track in 1957 and it was

re-centered in 1973 to allow for more generous clearances. In 1997 a

strip of stone was removed from the top of the tunnel and the tracks

were lowered to allow for even taller rail cars, and it is still in use

today.

|

This photo shows the

south portal of the Deer Creek Tunnel in approximately 1880. Gilbert

Avenue and the CL&N are climbing to Walnut Hills from left to right

and Reading Road, then known as Hunt Street, is in the background. From

"Narrow Gauge in Ohio" by John W. Hauck. |

Groundbreaking for the Deer Creek Tunnel took place

on December 16, 1852 at shaft number 2, located in the front yard of

2627 Stanton Avenue, which is now a vacant lot with a small community

garden. Four days later work was begun at the north portal and at shaft

number 1, which was in the middle of May Street, aligned with the south

property line of building 2333. Work on shaft 3, at the northwest corner

of Lincoln and Melrose, wasn't begun until February 15, 1853. Finally,

work on the south approach began on April 10 of that year. All three

shafts, which were of an elliptical profile 12 x 20 feet wide, were dug

to the location of the tunnel's crown between June 5 and 20 of 1853.

When all was said and done, the distance between portals, which includes

some completed cut and cover length on the south end, was 9,000 feet.

The south portal was at the location of today's northbound lanes of

I-71, where the ramp from northbound Reading Road merges into the

overpass at Florence Avenue. There was about 550 feet of open-cut

walled approach south of there, ending up in the southbound lanes of the

interstate just before the bridges for the Reading Road ramps. The

north portal was also buried by I-71 construction. It was located along

the left shoulder of the northbound lanes about 60 feet west of the

Blair Avenue overpass. Unlike at the south portal, none of the cut and

cover approach was built, so the north portal also marked the start of

the bored section of the tunnel. There was 583 feet of open-cut walled

approach north of here, with another 75 feet or so of retaining wall in

an open ravine. Prior to highway construction, the approach was filled

in to create yard space for nearby industries, though the tunnel was

apparently still visible in the 1950s. The buried approach walls could

still be there under the hillside north of I-71 in the headwaters of

Ross Run (commonly misnamed Bloody Run, which is farther north) that is

now mostly piped under Victory Parkway.

Digging was relatively easy through the soft clay,

shale, and occasional beds of limestone. Nevertheless, the tunnel was

still dug by hand using pick and shovel, with occasional use of black

powder for blasting and steam powered lifts to remove the spoils from

the vertical shafts and to provide fresh air to the workers. Under those

conditions, the going was certainly not swift. The company's second

annual report noted at the beginning of March in 1854 that 2,800 feet

had been excavated and 750 feet was entirely finished (meaning the

masonry walls and arching was in place). A year later, 3,336 feet of the

tunnel had been dug, with 1,514 feet of that being complete. A nominal

amount of horizontal digging was accomplished from shafts 1 and 2, while

significant northward progress had been made from shaft number 3.

By 1855 the project was slowing down due to

diminishing funds. A financial panic centered in Ohio in 1854 didn't

help. This panic led to bank failures in Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan,

and Maryland. The causes were a bank tax imposed several years earlier

and speculation in railroad securities. During the panic, banks in Ohio

relied heavily on their correspondent banks in New York City, resulting

in a drop in deposits and diminished investment funds for projects like

the Dayton & Cincinnati. Little to no work had been done on the

rest of the line, either north of the tunnel, where extensive cuts and

fills were needed to bridge the deeply cut ravines feeding into Ross

Run, or at the Broadway Street terminal where the casino is located

today. In June 1855, there was a cave in near the north portal which

killed five men who were prepping the ceiling for brick installation.

While the soft shale and clay was relatively easy to dig, it was still

unstable until the stone walls and brick arching could be installed.

Shortly thereafter, the project had to finally be abandoned for lack of

means, after $475,000 had been spent. This is not unlike the situation

of the Hoosac Tunnel in 1861, when its funding was pulled and the

company was bankrupted by unscrupulous competitors and the politicians

doing their bidding. While that project's chief promoter was elected to a

position that allowed him to revive the project, the Deer Creek Tunnel

had no such white knight.

In 1872, after more than 15 years of inactivity,

the enterprise was reorganized as the Cincinnati Railway Tunnel Company.

Some limited work began again, though it stopped in 1874 after little

additional progress had been made. There was another cave in near Oak

Street (presumably the north end of the tunneled section under shaft

number 2) in the intervening years as well, complicating efforts to

continue the project. The company became dormant again, and sale to

other interested parties was hampered by an excessive asking price for

the property.

By 1896, owners of the Cincinnati, Jackson & Mackinaw were trying to gain control of the CL&N,

which by then had built its own route down the Deer Creek Valley, with

two much shorter tunnels at a higher elevation. The CJ&M, unable to

buy out the CL&N, and dissatisfied with trackage rights to use

their Court Street terminal, attempted to secure the tunnel company for

their own entrance to the city. Calvin Brice of the CJ&M and his

associates gained control of the tunnel company by forcing it into

receivership after securing enough of the outstanding mortgage bonds to

demand foreclosure. On May 19, 1896 the tunnel company was sold to Ira

Bellows of New York, a covert associate of Brice. At the same time the

Pennsylvania Railroad was orchestrating its own purchase of the

CL&N, and it succeeded over Brice. The CJ&M was ultimately

foreclosed and reorganized, then it was acquired by the Big Four

in 1901. With no use for the unfinished tunnel or trackage rights over

the competing PRR/CL&N, the Big Four sold the tunnel property and

terminal land at Court Street to the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1902. Not

long after this time, much of the valley around the south portal was

filled with earth to create a level ball field called Deer Creek

Commons. Interest in the tunnel was briefly resurrected in 1927 by the

Beeler Report, a study of the Cincinnati subway rapid transit loop.

However, the deep location and sloping profile meant a station in the

tunnel would be impractical, and its incomplete status eliminated it

from any further consideration.

|

The south end of the

Deer Creek Tunnel was exposed during construction of I-71 in March 1966.

In the early 20th century the land around it was filled to a higher

level, burying the tunnel and its approach. From "Narrow Gauge in Ohio" by John W. Hauck, photo by Cornelius W. Hauck. |

For several decades knowledge of the tunnel

gradually faded. The south portal was buried under Deer Creek Commons,

and the north portal remained in obscurity buried under trees and brush

in the creek bed of a lonely industrial neighborhood. It is not known

what happened to the three vertical shafts in Walnut Hills. There are no

obvious manhole covers or other accesses, so they were most likely

filled in for being safety hazards.

In March of 1966 the tunnel was rediscovered by

construction workers excavating for I-71. A stretch of the tunnel near

the south portal was breached and quickly filled with dirt after a few

newspaper articles and some photographs were taken. The north portal was

also buried a few years later when highway construction reached

Avondale, and the remaining section of tunnel was blocked off by a

poured concrete bulkhead. About 550 feet of the north end of the tunnel

remains in place south of the bulkhead however, and as mentioned

already, the retaining walls for the north approach could very well

still be in place below the surface. In fact, because of the low grade,

the rest of the tunnel may still be in place under I-71 too, though

filled in. A similar situation might exist near the south portal as

well, since the highway bridge straddles the tunnel location somewhat.

On December 5, 2007 a backhoe that was excavating for the SpringHill

Suites Mariott partially fell into the south end of the tunnel near the

northeast corner of Florence Avenue and Eden Park Drive. Some brief

investigation was done, but it doesn't appear that any photographs were

taken. Controlled density fill, which is basically a weak form of

concrete, was dumped into the opening to secure the breach.

Nevertheless, about 500 feet of tunnel is probably still intact north of

there, ending under the north curb line of Florence Avenue near the

edge of the Cornerstone Insurance Broker parking lot and retaining wall.

The failure of this project is rather unfortunate,

to say the least. Had it actually been completed, the Deer Creek Tunnel

would have changed the shape of Cincinnati's growth immensely more than

the subway project 70 years later, in no small part because of its much

earlier influence on the region's development patterns. It's possible

the CH&D would be the only

mainline railroad in the Mill Creek Valley south of Sharonville. That

would certainly have impacted the valley's industrial growth, a great

deal of which would have shifted to Avondale, Evanston, Norwood, and

Bond Hill. No doubt it would also have greatly impacted the railroad

terminal pattern of the city. The Plum Street Station

would likely have remained a smaller facility for just two or three

railroads, rather than growing into the city's first union station.

Court Street would be much more important on the other hand, becoming

the de facto union station for Cincinnati, rather than a small depot for

a minor branch line and its one tenant. We would have seen much more

substantial connecting tracks along Eggleston Avenue from the Little Miami/Pan Handle

station, and perhaps a direct connection with a much more substantial

L&N bridge and associated viaducts, with more of the Kentucky

railroads feeding into that bridge and changing the development pattern

of Newport and Covington.

Even though the Deer Creek Tunnel was never

finished, plans were still floated in the early part of the 20th century

for a union station along the north end of downtown where Central

Parkway is today. Had the tunnel been finished, this plan would almost

surely have been implemented, using the drained canal bed for approach

tracks with through-running to the east and the west. Of course the

very ambitiousness and potential impacts of the Dayton & Cincinnati

Short Line was a primary factor in its ultimate failure. While new

railroads were being constructed into Cincinnati at the time, investors

were unwilling to jeopardize their previously made contributions to

competing railroad companies like the CH&D, Little Miami, or the Marietta & Cincinnati.

Financial blackballing by the relatively young but already powerful

interests of the existing and under construction railroads and their

financiers prevented the Dayton Short Line from raising enough capital

to finish its tunnel. We will never know for sure how things would be

different had the project been completed, but it is nonetheless a

fascinating thought.

Photographs and Diagrams

Return to Index